Gaining, Losing, and Winning Back the Vote: The Story of Utah Women’s Suffrage

Gaining, Losing, and Winning Back the Vote:

The Story of Utah Women’s Suffrage

By Barbara Jones Brown, Naomi Watkins, and Katherine Kitterman

Western suffragists, including Utahns Martha Hughes Cannon, Sarah M. Kimball, Emmeline B. Wells, and Zina D. H. Young, pose with national suffrage leaders Susan B. Anthony and Anna Howard Shaw at the 1895 Rocky Mountain Suffrage Meeting in Salt Lake City. Photo courtesy Utah State Historical Society.

When Utah became a U.S. territory in 1850, all free white male inhabitants over the age of 21 had the right to vote if they were U.S. citizens. This meant many groups of people (including women) were not legally allowed to vote. In the years that followed, Utah became a leader in women’s suffrage, a movement to gain the right to vote for women. Although Wyoming Territory was first in the nation to extend voting rights to women citizens in December 1869, Utah Territory did so several weeks later, on February 12, 1870. Since Utah held municipal elections and a territorial election before Wyoming did, Utah women earned the distinction of casting ballots first. Seraph Young, a schoolteacher, was the first woman to vote under a women’s equal suffrage law in the United States when she cast her ballot in the Salt Lake City municipal election on February 14, 1870.

Receiving the Vote: Enfranchisement (1870)

Several groups of people supported women’s suffrage in Utah for very different reasons. Some leaders of the national suffrage movement hoped that allowing women to vote in western territories such as Utah would pave the way for women’s suffrage in the rest of the nation. In 1869, these suffragists supported proposed bills in Congress to give Utah women the right to vote. Although the bills did not pass, they sparked discussion about the benefits of allowing women to vote in Utah.

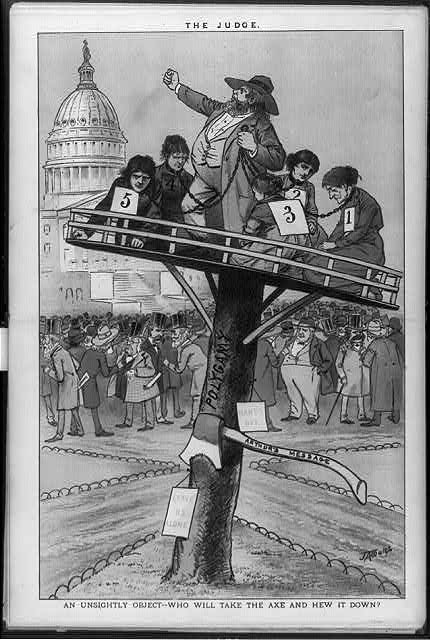

Artist unknown, “An Unsightly Object,” The Judge, 1882. Caption: “An Unsightly Object—Who Will Take an Axe and Hew It Down?”

The idea of women’s suffrage in Utah was linked with the Mormon practice of polygamy right from the start. In the late nineteenth century, members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints practiced polygamy, a marriage system in which a husband could have more than one living wife. Latter-day Saints, or “Mormons,” called it “plural marriage” and considered it a core religious belief. However, many Americans considered polygamy morally wrong and oppressive to women.

Back in 1856, the Republican party had declared its commitment to ending the “twin relics of barbarism, polygamy and slavery.” After slavery was abolished and Black men gained voting rights in the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, many American reformers turned their attention from ending slavery to ending polygamy. Initially, some believed that giving Utah women voting rights would politically empower them to end polygamy.

Latter-day Saints, on the other hand, believed that Mormon women would use their vote to show their support for polygamy. They also thought giving women the vote would change negative perceptions about the LDS Church and its treatment of women. They wanted to show that Utah women were not oppressed, helpless, and enslaved as many anti-polygamists believed. Finally, granting suffrage to Utah women (most of whom were Mormon) would strengthen support for the People’s Party, a Utah political party recently organized by Mormons in opposition to the new Liberal Party, formed by non-Mormon settlers whose numbers were increasing in Utah.

Some Utah women also supported women’s suffrage. For example, in January 1870, several thousand Mormon women gathered in Salt Lake City to protest an anti-polygamy bill being debated by Congress. The organizers of this women’s meeting voted to ask Utah’s territorial governor for the right to vote.

Emmeline B. Wells. Photo courtesy of LDS Church History Library.

On February 12, 1870, Utah’s acting Governor signed a Woman Suffrage Bill that had unanimously passed the Utah Territorial Legislature. This law extended voting rights in local and territorial elections to “every woman of the age of twenty-one years who has resided in this Territory six months next preceding any general or special election, born or naturalized in the United States, or who is the wife, widow or the daughter of a native-born or naturalized citizen of the United States.” The law did not extend the right to run for or hold public office. Seraph Young became Utah’s (and the nation’s) first female voter under an equal suffrage law two days later. Other women voted in municipal elections that spring, and thousands of Utah women cast ballots in the general election on August 1, 1870.

Gaining the vote broadened Utah women’s opportunities to participate in political life. Leaders of the Relief Society, the women’s organization of the LDS Church, developed programs to educate women about the political process and civic engagement. Utah women sent delegates like Emmeline B. Wells to represent them at national suffrage conventions and form ties with leading suffragists like Susan B. Anthony. However, Utah women did not vote for candidates opposed to polygamy like anti-polygamists had hoped.

Losing the Vote: Disfranchisement (1871-1887)

Since giving Utah women the vote did not end polygamy, anti-polygamists lobbied U.S. Congress to pass anti-polygamy laws pressuring the LDS Church to disavow polygamy. Several proposed anti-polygamy bills also included measures to revoke women’s suffrage. Many Utah women opposed these bills by holding protest meetings and petitioning Congress not to disfranchise them. Still, Congress passed the Edmunds-Tucker Act in 1887. Part of this legislation took away the voting rights of all Utah women, whether they were Mormon or not, polygamous or monogamous, married or single.

Winning Back the Vote: Re-enfranchisement (1887-1896)

Left to Right: Emily S. Richards (co-founder of Utah Woman Suffrage Association), Phebe Y. Beattie (executive committee chair of UWSA), and Sarah M. Kimball (second president of UWSA). Photo courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

Utah women had been voters for seventeen years, so many of them were outraged when Congress took those rights away. They worked hard to win suffrage back. They created the Woman Suffrage Association of Utah, an affiliate of Susan B. Anthony’s National American Woman Suffrage Association, and organized local chapters throughout the territory. However, not all women in Utah wanted women’s suffrage. Some opposed it because they thought Mormon women’s votes would continue to uphold polygamy, while others thought women should not be involved in politics.

In 1890, LDS Church president Wilford Woodruff officially ended the practice of polygamy. With this change in policy, Congress passed the 1894 Enabling Act, inviting Utah to again apply to enter the Union as a state. (Congress had rejected Utah Territory’s prior attempts over the previous four decades, largely because of polygamy.) During Utah’s 1895 Constitutional Convention, delegates debated whether to include women’s suffrage and right to hold public office in the state constitution that Utah would propose to Congress.

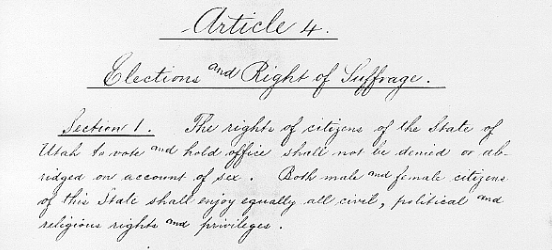

In contrast to other parts of the nation, most Utahns supported a woman’s right to vote and hold office. Both national political parties in Utah–Democrat and Republican–supported these rights in their party platforms, and women’s suffrage organizations throughout the territory lobbied delegates to include these rights in Utah’s constitution. Despite minor opposition, the delegates voted to include a clause in the constitution that granted women’s suffrage and the right to hold office. Article 4, Section 1 of the Utah Constitution states: “The rights of citizens of the State of Utah to vote and hold office shall not be denied on account of sex. Both male and female citizens of this State shall enjoy equally all civil, political and religious rights and privileges.” A few months later, Utah’s male electorate voted overwhelmingly to approve the proposed constitution. Utah women regained the vote, or were re-enfranchised, when Congress accepted Utah’s constitution and granted Utah statehood in 1896.

Article 4, Section 1 from the Utah State Constitution, Elections and Right of Suffrage. Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

Utah Women and the National Suffrage Movement (1896-1920)

When Utah gained statehood, only two other states–Wyoming and Colorado–allowed women to vote. Suffragists across the nation were still working toward a constitutional amendment for women’s suffrage. Many Utah women continued to work with national suffrage organizations by providing funding, serving in leadership positions, circulating petitions, and attending and speaking at national and international women’s rights conventions.

More than 70 years after the women’s rights movement began, Congress ratified the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in August 1920, granting women’s suffrage throughout the nation. It states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

Members of the executive committee of the national suffragists’ convention and prominent local suffragists snapped this photo with Senator Reed Smoot in August 1915 outside of the Hotel Utah, after meeting with him to ensure his support for a federal women’s suffrage amendment in the next Congress. From L to R: Marie Mahon of New York, Hannah S. Lapish, Emmeline B. Wells, Senator Reed Smoot, Lily C. Wolstenhome, Elizabeth Hayward, Margaret Zane Cherdron, Lucy A. Clark, Mrs. J. H. Saxson, Mrs. A. D. Paine, Lillie T. Freeze, Ruth M. Fox, Mrs. Charles Livingston, Mrs. L. R. Tanner, and Mrs. M. B. Lawrence. Photo courtesy of the National Woman’s Party.

After 1920: The Struggle for Minority Voting Rights Continues

Although the 19th Amendment granted women’s suffrage nationally, the fight for universal suffrage in the United States was not over. Not all women residing in Utah were granted the vote in 1870 or with statehood in 1896 or with the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

Though the 14th Amendment had earlier defined “citizens” as any person born in the United States, the amendment was interpreted to restrict the citizenship rights (including the right to vote) of many. For example, since Native Americans were not considered U.S. citizens during this time period, they were excluded from women’s voting rights in Utah in 1870 and 1896, and nationally in 1920. Legal barriers enacted in numerous states effectively made it impossible for African Americans to vote. Many Asian immigrants in the United States were legally prohibited from applying for citizenship (and gaining voting rights) simply because of their countries of origin.

President Lyndon Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act of 1965 with Civil Rights Leaders, including Dr. Martin Luther King. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

These minority groups strengthened their rights to citizenship and voting through the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 (which granted full citizenship to indigenous people born in the U.S.), the McCarran–Walter Act of 1952 (which permitted Asian immigrants to become naturalized citizens), and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (which prohibited barriers at state and local levels that prevented African Americans from exercising their suffrage rights).

Even after the passage of the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act, many states, including Utah, still made local laws and policies that prohibited Native Americans from voting, arguing that Native Americans living on reservations were residents of their own nations and thus non-residents of the states. On February 14, 1957, the Utah state legislature repealed its legislation that had prevented Native Americans living on reservations from voting, becoming one of the last states to do so.

Utah Women Today

The work continues for women’s rights and minority rights in Utah and throughout the nation. The year 2020 will mark the 150th anniversary of women first voting in Utah and the 100th anniversary of women voting nationally. As we celebrate and learn about these historical events, the sacrifices and commitment of Utah’s strong women in the past will inspire Utah’s strong women of today. We envision a bright future for Utah as women become more engaged participants in our communities. As in the past, the passionate involvement of women and men working together to elevate women’s status will bring about better days for Utah.