Contention At The Convention

Contention at the Convention

By Sarah Hancock Jones

October 18, 2018

Filing into the Salt Lake City and County building in the spring of 1895, Utah women thought they had it in the bag. They had been working for years to build support for universal suffrage in the state constitution: collaborating with national leaders like Susan B. Anthony, writing and publishing their own newspaper, the Woman’s Exponent, to convince the masses, and building local coalitions of men and women devoted to the cause. Utah women had even banded together to lobby the men who were elected as delegates to write the new state constitution to ensure they were sympathetic to the inclusion of female suffrage. And finally, the day arrived that the issue would be debated at the state constitutional convention. The room was packed. Crammed in were not only male delegates with the power to create the constitution but also female suffrage leaders who could only watch.

Delegates to the Constitutional Convention, 1895. The two women were convention clerks.

The women watching the men debate knew how vital it was to ensure that the original state constitution include voting rights for women. It was much easier to create a constitution with equal voting rights than modify one to add those rights later. Women in Utah and won the right to vote relatively easily in 1870, but then that right had been stripped away seventeen years later by the federal Edmunds-Tucker Act of 1887. In the years since, women had united under energetic and articulate leaders such as Emmeline B. Wells, Emily Richards, and many others, who argued that they had voted responsibly for nearly two decades. Their second main argument was a direct jab at the federal government: due to the Edmunds-Tucker Act, which led to the end of Mormon polygamy, there were more female-led households and therefore more women working and being taxed in Utah than in any other state in the Union. Those women deserved the right to vote. Surely, as the new state constitution was drafted, it should restore to women their voting rights.

Well, the women and their supporters were shocked when one of the delegates, 38-year-old B.H. Roberts, flatly opposed including female suffrage in the constitution and instead argued that it should be included as an amendment, which delegates could vote on separately. As B.H. Roberts’ arguments began to gather momentum among the group of all-male delegates, the women, who had worked tirelessly since their rights were revoked in 1887, were exasperated. Franklin Richards, husband to suffragist Emily Richards, stood firm against the unfair arguments, submitting to the delegation that it should “provide in the constitution that the rights of citizens of the State of Utah to vote and hold office shall not be denied or abridged on account of sex, but that male and female citizens of the state shall equally enjoy all civil, political, and religious rights and privileges.” The leaders of Utah’s suffrage organizations signed this pleading.

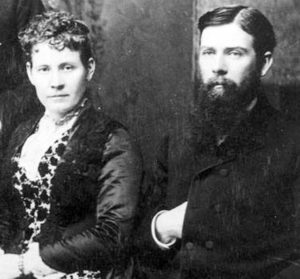

Emily S. and Franklin S. Richards

The debates ended for the day and the women left, most likely feeling frustrated and helpless. How could they ensure that their rights would make it in the constitution when they didn’t even have a way to vote on the matter directly? The next morning, March 19, suffrage supporters were granted a hearing before the delegates, and seven women, including Emily Richards and Emmeline B. Wells, made compelling speeches laying out the facts of their case and imploring that the delegates be just in their decision. Their speeches inspired quite a bit of debate among the male delegates, which the women had to simply witness, as they were no longer allowed to speak. During this debate delegate Orson F. Whitney insisted, “I believe in a future for woman…I do not believe that she was made merely for a wife, a mother, a cook, and a housekeeper. These callings, however honorable…are not the sum of her capabilities.” He went on to argue, “They tell us that woman suffrage in the Constitution will imperil Statehood. I don’t believe it. But if it should, what of it? There are some things higher and dearer than Statehood. I would rather stand by my honor, by my principles, than to have Statehood.”

Orson F. Whitney

That day, female suffrage was issued a favorable report, meaning it would be included in the constitution when it was eventually voted upon. However, B.H. Roberts and a small group of delegates continued to work against the adoption of the article throughout the following weeks. Female leaders gathered petitions urging for the adoption of the article. They did not give up the fight. The final vote for the suffrage article was held April 8, and a 15-minute debate was allowed. Emmeline Wells described the hall as “crowded to suffocation.” Having already hashed out the main points just a few months previously, the delegates quickly moved to vote, and finally, after years of work and effort, the vote of the Utah delegates regarding female suffrage was 74 yes, 6 no, and 12 absent. The numbers reflect consensus, but they don’t show the full story. Those 74 yes votes were a direct result of Utah women’s devotion to the cause of universal suffrage for many years.

Sarah Hancock Jones is an English and reading teacher to some excellent junior high students. She’s passionate about teaching literature, swimming in Utah’s gorgeous lakes and reservoirs, and searching for the most delicious pizza joint.

Further Reading:

Emmeline B. Wells, “The History of Woman Suffrage in Utah: 1870-1900,” in Battle for the Ballot ed. Carol Cornwall Madsen (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1997), 33-51.

“Proceedings and Debates of the Convention Assembled to Adopt a Constitution for the State of Utah,” March 4, 1895 – May 8, 1895.

Franklin Richards quotations from the constitutional convention proceedings of March 28, 1895.

Orson F. Whitney quotations from the constitutional convention proceedings of March 29, 1895 and April 5, 1895.