The Suffrage Resolution at Seneca Falls

By Candace Brown, Better Days 2020 Historical Intern

July 27, 2018

On July 19, 1848, in the opening speech of the Seneca Falls Convention, Elizabeth Cady Stanton declared, “We [women] now demand the right to vote.” Her audience applauded her gumption. But when she later presented the ninth resolution in her Declaration of Sentiments, “Resolved, That it is the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise,” they recognized her statement for what it was: A call to action. Few felt ready to answer.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton with two of her children, Henry and David, around the time of the Seneca Falls Convention. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

Like Stanton, those attending America’s first women’s rights convention saw the absurdity and harm in the social subjugation, moral double standards, and legal inequalities imposed on women. They recognized an urgent need for change and wanted to help.To this end they quickly and unanimously ratified every paragraph of Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s Declaration of Sentiments, a document Stanton created to be the rally point and guide for the women’s movement. In the spirit of the Declaration of Independence, the Declaration of Sentiments included a list of women’s grievances, such as routinely losing custody of their children after a divorce, and also a list of resolutions, such as improving civic education for women, each of which was wholeheartedly supported by the convention. Except for the ninth resolution.Lucretia Mott was a revolutionary Quaker minister and a leading American abolitionist. She helped to organize the Seneca Falls Convention and seemed to embody American idealism. But when she heard the ninth resolution for the first time, she turned to Stanton and said, “Why Lizzie, thee will make us ridiculous.” American women didn’t vote. To insist on women’s suffrage was to flout countless cultural norms and invite public ridicule from the press, politicians, preachers, and especially spouses.

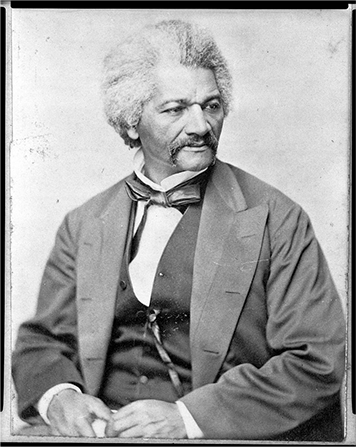

Frederick Douglass, respected abolitionist and supporter of women’s suffrage, 1870. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

Mott and the other women knew that their inability to vote and represent themselves in the government was the root of most sex-based legal discrimination. They also knew the backlash against the demand for suffrage would be fierce and unforgiving. And in the end, a ballot was just a piece of paper.Frederick Douglass disagreed. And he said so. After listening to as much as he could stand of the arguments against the resolution, the former slave and prominent abolitionist stood and spoke. He passionately defended women’s suffrage not only as the way to right a wrong but also as the way to heal a wound. He said, “In this denial of the right to participate in government, not merely the degradation of woman and the perpetuation of a great injustice happens, but the maiming and repudiation of one-half of the moral and intellectual power of the government of the world.”

What Stanton understood and Douglass articulated was that the right to vote, the right to fill out a slip of paper and put it in the ballot box, was more than just a symbol of equality. It was a symbol of power, a physical representation of women’s right to be more than second-class citizens. It was a tool, a way to hold lawmakers accountable for ending sex-based legal and social discrimination. It was an invitation for women to gain the confidence and self-respect they’d so often been denied. It was an opportunity for women to take responsibility for their lives, live up to their moral and intellectual potential, and become forces for good in America. Suffrage was the key. With it, women could thrive at home, at school, at work, in court, and ultimately even on Capitol Hill.

The Declaration of Sentiments was reprinted in the official convention report. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

After Douglass sat down, Stanton submitted the ninth resolution to the convention again. They ratified it by a large majority, committing themselves to over seventy years of lobbying, petitioning, and marching for the right to vote. As expected, they were constantly ridiculed for their efforts, mocked and chastised in print, over pulpits, and in their own homes. But they were sustained, as Douglass said in 1888, by “a firm conviction that [they] were in the right, and a firm faith that the right must ultimately prevail.” Less than fifty years later, that faith was partially realized during Utah’s first state election in 1896. For the first time in American history, thousands of male and female voters selected a woman, Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon, as state senator, evidence that Stanton’s call to action had been heard and women and men were ready to act.

Candace Brown recently graduated from Timpview High School in Provo, Utah and is now a student at Brigham Young University. Raised in Utah, she enjoys learning about and sharing the history of women’s suffrage in the Beehive State.

Further Reading:

“Report of the Woman’s Rights Convention.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, www.nps.gov/wori/learn/historyculture/report-of-the-womans-rights-convention.htm.

Hillary Rodham Clinton, Remarks, “150th Anniversary of the First Women’s Rights Convention,” delivered 16 July 1998, Seneca Falls, NY.

1. Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. Address Delivered at Seneca Falls and Rochester. New York: R.J. Johnston. 1870. Print. http://ecssba.rutgers.edu/docs/seneca.html

2. “Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions.” Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions, Seneca Falls: Stanton and Anthony Papers Online, ecssba.rutgers.edu/docs/seneca.html.

3. McMillen, Sally G. Seneca Falls and the Origin of the Women’s Rights Movement. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. Print. (p. 93)

4. McMillen, Sally G. Seneca Falls and the Origin of the Women’s Rights Movement. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. Print. (pp. 93-94)

5. “Frederick Douglass on Woman Suffrage: 1888.” Social Welfare History Project, 13 Mar. 2018, socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/woman-suffrage/frederick-douglass-woman-suffrage-1888/.