The Anti-Polygamy Society and Utah Women’s Suffrage

By Gabi Price

November 29, 2018

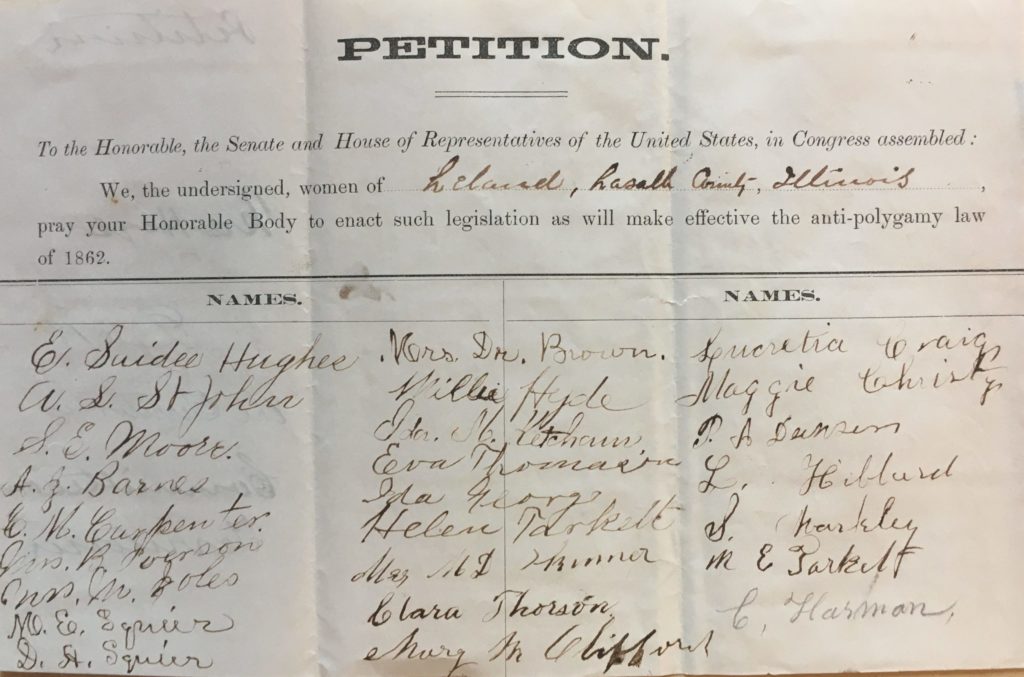

Anti-polygamy petition to Congress from the women of Leland, Illinois, 1879. Document held in the National Archives.

In February of 1870, Utah territory granted Utah women citizens the right to vote. Many Americans hoped that Utah women would use their votes to help end the common Mormon practice of polygamy, or plural marriage, believing that it did not align with the goals of enfranchised women, who would surely vote in favor of anti-polygamy legislation. Mormon legislators in Utah hoped that giving Utah women suffrage would prove that they were capable and competent voters, show the rest of the country that Utah women were happy with their situation, and decrease anti-polygamy sentiment in the nation. While there were opponents of polygamy both outside and inside Utah, no organization in the territory actively worked against the practice until the formation of the Ladies’ Anti-Polygamy Society of Utah in 1878. The society was comprised of women who met to write letters, petition, and speak on matters of legislation that would promote the end of polygamy.

In 1878, an event occurred that ignited the anti-polygamists of Utah to organize in denouncing the practice of plural marriage. After traveling from England to marry a man she had reconnected with while he was serving a LDS mission in her town, Caroline Owens learned her future husband was engaged to two other women. Just hours after she was wed, she fled and sought counsel from a few non-Mormon women in the area. There were no witnesses, no marriage records at the time, and there was no legal case that could be made due to the lack of evidence and the inability for a woman to legally testify in the Utah territory without the permission of her husband.

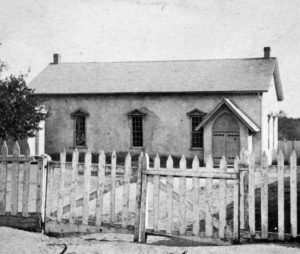

Independence Hall in Salt Lake City. Photo courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

In reaction to this incident, on November 7, 1878 several women met in Salt Lake City’s Independence Hall to write a letter to the nation’s first lady, Mrs. Rutherford B. Hayes, the United States Congress, and various clergy urging them to update and enforce anti-polygamy legislation. The Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act of 1862 should have made it illegal for polygamists to vote and hold office. However, President Lincoln had chosen not to enforce the law as long as Utah refrained from becoming involved in the Civil War. Now, the Anti-Polygamy Society requested federal action. Thirty thousand copies of the letter from the Ladies Anti-Polygamy Society were distributed throughout the nation. The letter made the presence of anti-polygamists in Utah known, and pledged the support of these women in the national effort to end polygamy. Petitions flooded into Congress from women across the country asking for stricter anti-polygamy laws.

Jennie Anderson Froiseth. Photo courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

Sarah A. Cooke and Jennie A. Froiseth, who led the Society, were aware that their petitions for anti-polygamy legislation could potentially limit rights of women in their territory; however, their belief was that Mormon women who practiced or believed in polygamy were too influenced by their religion to have the vote. Froiseth went on to publish and edit an anti-polygamy newspaper for the society in 1880, the Anti-Polygamy Standard, which lasted a short three years but had a great impact on the society and its national work. The Standard aimed to educate people on polygamy in Utah and report on what the Ladies’ Anti-Polygamy Society was doing to implement change. Froiseth was passionate about women’s rights; she served as a Utah delegate to the National Woman Suffrage Association and became the association’s vice president for Utah in 1888. Still, her whole-hearted work against the institution of polygamy often created conflict between her and other Utah suffragists.

The Anti-Polygamy Society was determined to end polygamist control in Utah by promoting national efforts to enforce anti-polygamy legislation, and by working to elect officials to represent Utah who were not influenced by the Mormon church. In 1881, the society urged American women to write to their representatives to support Allen Campbell as the representative for Utah Territory over George Cannon, a polygamist. Neither representative was chosen and the congressional seat was not filled. However, in March of 1882, the goals of the anti-polygamists were partially achieved with the passing of the Edmunds Act. The act reinforced the principles of the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act, made polygamy a felony under federal law, and initiated the arrest of many polygamist men. Women were viewed as victims of polygamy and were not charged at this time, but both polygamous men and women lost the right to vote, serve on a jury, or hold public office. Five years later, the Edmunds-Tucker Act disfranchised all Utah women, married or single. Many Utah women were outraged to lose their rights, and they set their sights on ensuring women’s suffrage was protected in a future Utah state constitution. However, Froiseth and several other prominent Utah women refused to work alongside Mormon suffragists until after the church officially ended the practice of polygamy in 1890.

As Utah was invited to apply for statehood in 1894, many suffrage supporters came together in the Utah Woman Suffrage Association, regardless of their earlier division over polygamy, to lobby for the inclusion of women’s suffrage in the new state constitution. During the 1895 constitutional convention, a suffrage clause was included that enfranchised all female citizens of Utah. In 1896, Utah became the third suffrage state and 45th state in the United States of America.

For more information on the anti-polygamy movement and its effect on Utah women’s suffrage, read “Receiving, Losing, and Winning Back the Vote: The Story of Utah Women’s Suffrage” and check out our FAQs.

Gabi Price is a history student at the University of Utah. Having been surrounded by powerful, smart, and influential women her whole life, she appreciates the opportunity to learn about Utah women who made history and research those who have yet to be discovered.