Utah and Native American Voting Rights

By Jennifer Robinson

March 28, 2019

“..a group denied the effective exercise of the vote is necessarily deprived of the ability to protect its rights. Because elected officials are free to disregard its needs and concerns, a disfranchised group is denied an effective voice in policy-making decisions and is relegated to second-class status.”¹

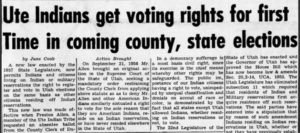

Utah women were the first to vote in the modern nation, but the state has an unfortunate track record with Native American voting rights. A Utah law, passed shortly after statehood, prohibited Native Americans who resided on a reservation from voting. The law remained in place until 1957. The law stated that “any person living upon any Indian or military reservation shall not be a resident of Utah, within the meaning of this chapter, unless such person had acquired a residence in some county prior to taking up his [or her] residence upon such Indian or military reservation.”²

In 1940, Joseph Chez, the Attorney General for the State of Utah, issued an opinion that Native Americans, both those living on and off reservations, should be allowed to vote. The Attorney General argued this because “the attitude of the Government towards Indians themselves with relation to voting privileges has changed materially since the Utah statute in question was created.”³ Native Americans were permitted to vote from 1940 until 1956, when a second, and contradictory, opinion was issued by Attorney General E. R. Callister. Callister’s opinion simply stated that the “Indians who live on the reservations are not entitled to vote in Utah… Indians living off the reservation may, of course, register and vote in the voting district in which they reside, the same as the same as any other citizen.”4

That same year, Preston Allen, a Native American living on the Uintah and Ouray Reservation, challenged the Utah law as violating the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments of the U.S. Constitution. The Utah Supreme Court ruled against Allen, distinguishing Native Americans living on reservations from other citizens. The court relied upon three arguments for upholding the statute: 1) Native Americans living on reservations are members of tribes “which have a considerable degree of sovereignty independent of state government”; 2) the federal government remains largely responsible for the welfare of Native Americans on the reservations and maintains a high degree of “control over them”; and 3) Native Americans living on reservations are “much less concerned with paying taxes and otherwise being involved with state government and its local units, and are much less interested in it than are citizens generally.”5 The case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court; however, before the Court could act, the Utah Legislature removed the prohibitory language from the state code in 1957.

That same year, Preston Allen, a Native American living on the Uintah and Ouray Reservation, challenged the Utah law as violating the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments of the U.S. Constitution. The Utah Supreme Court ruled against Allen, distinguishing Native Americans living on reservations from other citizens. The court relied upon three arguments for upholding the statute: 1) Native Americans living on reservations are members of tribes “which have a considerable degree of sovereignty independent of state government”; 2) the federal government remains largely responsible for the welfare of Native Americans on the reservations and maintains a high degree of “control over them”; and 3) Native Americans living on reservations are “much less concerned with paying taxes and otherwise being involved with state government and its local units, and are much less interested in it than are citizens generally.”5 The case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court; however, before the Court could act, the Utah Legislature removed the prohibitory language from the state code in 1957.

The importance of pursuing voting rights for Native Americans remains to this day. At least 90 voting rights cases have been filed on behalf of Native Americans across the nation between 1965, the year the Voting Rights Act passed, and 2016.6 When discriminatory structures and procedures are dismantled, American Indians are able to fully realize their rights as guaranteed by the Constitution. Indeed, the right to vote “is regarded as a fundamental political right, because [it is] preservative of all rights.”7

Jennifer Robinson is the associate director of the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute at the David Eccles School of Business. She is the co-author of Native Vote: American Indians, the Voting Rights Act, and the Right to Vote and numerous book chapters and articles on voting rights.

- McDonald, Laughlin. 2010. American Indians and the Fight for Equal Voting Rights. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- An Act Providing for Elections 1897, 172.

- Opinion of the Attorney General of Utah, October 25, 1940. At the time, eight other states denied Native Americans the right to vote using residency, taxation, guardianship, literacy requirements, and/or tribal ties to prevent Native Americans from voting.

- Opinion of the Attorney General of Utah, March 23, 1956.

- Allen v. Merrell, 1956.

- Utah cases include: Yanito v. Barber 1972; U.S. v. San Juan County, Utah, 1983 (vote dilution case); U.S. v. San Juan County, Utah, 1983 (Section 203 language case); Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission v. San Juan County, 2017; and Navajo Nation v. San Juan County, 2016.

- Yick Wo v. Hopkins (1886).