A Path Forward—Utah’s New Women’s History Memorial

We’re thrilled with the new memorial to Utah women’s history! We unveiled this gift from Better Days 2020 to the state of Utah in a special ceremony for the centennial of the 19th Amendment in August 2020. “A Path Forward” was created by artists Kelsey Harrison and Jason Manley to honor Utah women’s contributions to the movement for equal voting rights. You can read their artists’ statement here. You can watch our virtual field trip here or read the following adaptation from the historical narration read by Dr. Jackie Thompson at the unveiling.

All photos courtesy of Dave Brewer, Photo Collective Studios.

The sculpture stands in front of Council Hall in Salt Lake City, where Seraph Young and 25 other women became the first in the United States to vote under an equal suffrage law when they cast ballots on February 14, 1870. Seraph’s footsteps mark a significant milestone on the path forward for women’s voting rights, and they’re represented at the beginning of the memorial. The expansion of voting rights to include female citizens was controversial at the time, and Utah women fought to retain and then regain that right. More on that story here.

The Richards’ great-great granddaughter Jody Nelson and fourth-great granddaughter Sophie.

Utah women citizens voted for 17 years, but Congress revoked their voting rights as part of federal anti-polygamy legislation in 1887. Emily S. Richards led suffragists in organizing the Woman Suffrage Association in 21 Utah counties. WSA members gave speeches, signed petitions, met with lawmakers, and held events and parades to keep the issue in the public eye. Emily and her husband Franklin were instrumental in securing women’s equal voting rights in Utah’s state constitution in 1895.

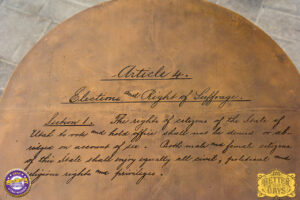

The chairs in the memorial are bronze replicas of chairs in the Salt Lake City and County Building, where the state constitution was debated and drafted. The table is patterned after the tea table in Seneca Falls where Elizabeth Cady Stanton drafted the Declaration of Sentiments, and Article 4 of Utah’s state constitution is engraved on the top, stating: “The rights of citizens of the State of Utah to vote and hold office shall not be denied or abridged on account of sex. Both male and female citizens shall enjoy equally all civil, political and religious rights and privileges.”

The chairs in the memorial are bronze replicas of chairs in the Salt Lake City and County Building, where the state constitution was debated and drafted. The table is patterned after the tea table in Seneca Falls where Elizabeth Cady Stanton drafted the Declaration of Sentiments, and Article 4 of Utah’s state constitution is engraved on the top, stating: “The rights of citizens of the State of Utah to vote and hold office shall not be denied or abridged on account of sex. Both male and female citizens shall enjoy equally all civil, political and religious rights and privileges.”

Elizabeth Hayward’s 4th-great granddaughter Becky Seamons and her daughters Skye, Adrie, and Katie.

After statehood, Utah women still worked for a women’s suffrage amendment to the U.S. constitution that would further protect their voting rights. They continued to lobby, petition, parade, and even protest until the 19th Amendment eventually became law on August 26, 1920, stating: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” Utahns had already elected 16 women to the state legislature and over 120 to county offices before 1920. State senator Elizabeth Hayward and three other female legislators led Utah’s ratification process for the 19th Amendment in the fall of 1919.

This first doorway in the sculpture represents the 19th Amendment. It’s surrounded by a wall of words made of quotes from state and national suffrage leaders like Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, Martha Hughes Cannon, Lucretia Mott, Emmeline B. Wells, Charlotte Godbe, Franklin Richards, and Sarah M. Kimball.

This first doorway in the sculpture represents the 19th Amendment. It’s surrounded by a wall of words made of quotes from state and national suffrage leaders like Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, Martha Hughes Cannon, Lucretia Mott, Emmeline B. Wells, Charlotte Godbe, Franklin Richards, and Sarah M. Kimball.

The ratification of the 19th Amendment one hundred years ago was a huge step forward—it was the largest enfranchisement of new voters in U.S. history! But the Amendment alone did not achieve equity in voting for all women. Many women (and men) were still denied access to the polls due to their race or national origin. Suffrage work continued as Americans fought for legislation expanding voting rights, represented in this memorial by expanding doorframes and a widening path moving forward toward the State Capitol.

Violet Bear Allen’s daughter Mary Allen and grandson Kai Allen.

The second doorframe reflects the fact that Indigenous women and men and their allies continued to fight for their voices to be heard and their votes counted. The Indian Citizenship Act conferred U.S. citizenship on all American Indians for the first time in 1924. But many states still had laws that prevented residents of reservations from voting—Utah only repealed its law in 1957. Indigenous nations and tribes in this region have been led by women for centuries. As this leadership converged with the recognition of citizenship from the federal and state government, leading women like Violet Bear Allen of the Skull Valley Goshute Tribe continued to preserve Indigenous arts and culture and encourage everyone to use their voice to improve conditions in their community.

Alice’s daughter Kimi Kasai, granddaughters Pat Ninomiya and Sheila Ju, and great-grandsons Bennet and Ty Chew.

The third doorway represents the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952. Until that time, the U.S. prohibited women and men from many Asian countries from emigrating to the U.S. or applying for U.S. citizenship. Utahn Alice Kasai was one of many people who advocated for laws that would get rid of those discriminatory practices. The 1952 law still reflected many racial prejudices in immigration quotas, but it did open up a pathway for citizenship and voting rights for many Asian-Americans, including Alice’s husband Henry, who had been born in Japan. Henry had been imprisoned by the U.S. government during World War Two, and Alice had led the Japanese American Citizens League in Salt Lake City to fight against discrimination and build bridges of peace and understanding.

Mignon Richmond’s family including great nieces Jodi Smith and Meloni Nebeker, and great-great niece Shaunte McGee.

The last doorway in the memorial commemorates the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965. 55 years ago, the Act declared poll taxes and literacy tests illegal and gave the federal government the authority to intervene in state voting regulations on behalf of marginalized communities. This law helped to dismantle undemocratic state policies and procedures that had made voting virtually impossible for thousands of eligible Black voters and people of color, especially in the South. Millions more people were now able to register and vote. Mignon Barker Richmond and other Black community leaders had voting rights in Utah, but worked through the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to combat discrimination and fight for equal access in employment, housing, education, and public services.

10 years later, in 1975, an extension of the Voting Rights Act was passed that prohibited discrimination in voting based on language barriers. This provided much needed voting rights protection to Hispanic, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander and Indigenous people throughout Utah and the U.S. It opened up avenues for translating voter registration information into multiple languages, and established foundations for challenging other discriminatory practices that infringed on voting rights. Edith Melendez organized efforts to advocate for the Hispanic community here in Utah during this time, advocating for equal opportunities in jobs, education, and social services.

The last part of the memorial brings us to the present day. It’s perfectly fitting that the exit of the memorial faces the Utah State Capitol, where public policy is debated and established today. That’s where this expanding path of voting rights leads! As we commemorate 150 years of Utah women voting, we acknowledge the tens of thousands of women (and men) whose efforts and activism provide the foundation for our participation in the elective process today. We hope this memorial inspires you to add your voice to those represented in this memorial. The story of suffrage in Utah is the story of each of us, individually and collectively, as we continue to engage in the work of establishing strong communities where all voices are heard.

The last part of the memorial brings us to the present day. It’s perfectly fitting that the exit of the memorial faces the Utah State Capitol, where public policy is debated and established today. That’s where this expanding path of voting rights leads! As we commemorate 150 years of Utah women voting, we acknowledge the tens of thousands of women (and men) whose efforts and activism provide the foundation for our participation in the elective process today. We hope this memorial inspires you to add your voice to those represented in this memorial. The story of suffrage in Utah is the story of each of us, individually and collectively, as we continue to engage in the work of establishing strong communities where all voices are heard.

Artist Kelsey Harrison, representatives from J.B. Lawnworks and Baer Bronze who helped fabricate the memorial, and artist Jason Manley.