Additional Resources

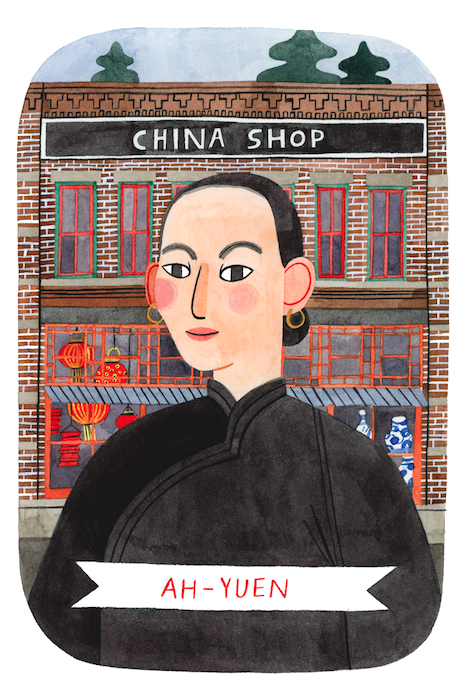

Ah-Yuen,

A Rare, Historical Find

ca. 1848 to 1854 -- 1939

by Christopher Merritt

That Utah history notes the life and successes of Ah Yuen, sometimes called China Mary, is surprising. During the 1880s, Ah Yuen and her husband ran a “China Shop” in Park City, catering to both European-American and Chinese tastes. Like many Chinese in the 19th and 20th centuries, Ah Yuen barely exists in the historical record. Racist biases at the time did not include the Chinese often in newspaper or written accounts, and immigrant laws restricted the number of Chinese women that could even enter the United States. Even her full name is not fully known and she appears as “Mary Susa”, “China Mary”, and “Ah Yuen” in the census records of Utah and Wyoming. What we do know of Ah Yuen, is that she arrived in the United States between 1863 and 1868, at the peak of pre-Transcontinental Railroad era immigration, after likely being born in southeast China between 1848 and 1854.[i]

Ah-Yuen. Photo courtesy of Find A Grave.

After arriving in the United States in the 1860s, she traveled from San Francisco, California to Park City, Utah by the 1880s and started a “China Shop” with a wealthy, but unknown Chinese husband. Chinese stores of the type operated by Ah Yuen dealt in silks, dishes, Chinese and Japanese tableware and foods, and other sundry articles that appealed to a wide customer base. Because of the mining boom in Park City, there were well over 400 Chinese residents of the bustling town during the 1880s and 1890s, representing likely the largest or second largest Chinatown in Utah Territory.[ii]

Around 1900 it appears that Ah Yuen left Park City, possibly after the death of her first husband. Moving to Evanston, Wyoming, she would marry twice more. Her final husband appears to be a gardener, and she spent the rest of her life in Evanston, until her death on January 13, 1939 at an age estimated between 85 or 91 (though her obituary states she was over 100).[iii] By her death she had become a known and loved fixture of Evanston, and her funeral was overseen by a Presbyterian Minister. Ah Yuen’s story, while ending as a simple gardener in Wyoming, speaks to the hard life and varied successes of Chinese women in the United States. So small in number and forgotten in nearly all parts of history, Chinese women were perhaps the most hidden, exploited, and ignored parts of Utah’s 19th century history. Her life represents many of the other Chinese women who came to the United States in search of new lives and opportunities.

Why did Ah Yuen or other Chinese immigrants leave in China in the 19th century? Facing mounting violence from a civil war, rampant unemployment, dispossession of land and wealth, famine, and overpopulation of coastal cities, millions of predominantly poor Chinese immigrants left their homes in search of opportunity in overseas countries. Between the 1840s and 1860s, historians estimate that nearly 20 million Chinese died in a series of violent civil wars, with another 30 million falling into a status that we would call refugees today.[iv] From the swelling port cities of southeastern China, tens of thousands of Chinese immigrants headed to points overseas including the United States to mine for gold, build railroads, work in factories, and even continue to practice farming.

Why is Ah Yuen’s story significant? In order to understand that question, we need to understand the broader historical context around her immigration. Historical records of Chinese immigrants is spotty at best, and for women, this situation is even worse. Most of the Chinese arriving in the United States after the 1849 gold rush in California were working class and economically disenfranchised men seeking financial successes for their families back home. With the cost of boat fare, very few Chinese women came to the United States except through wealthier families. However, the 1875 Page Act passed by U. S. Congress banned the immigration of Chinese women into the United States after labeling them all as prostitutes.[v] This was a specific attempt by Americans to keep Chinese men as a cheap labor pool, but limit the potential of these immigrants from staying and starting families. Making things worse, the 1882 passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act stopping the immigration of any working class Chinese man destroyed the potential for communities here in the United States.[vi] The Exclusion and Page Acts were the first two federal laws targeting a specific nationality.

Chinese in the United States, both men and women, suffered from the impacts of these restrictive Acts. In 1880 the Chinese population of the U.S. peaked at 103,620, but heavy-handed enforcement of these laws collapsed the population to 53,891 by 1920. Utah did not fare better, with a population of 806 Chinese in 1890 dropping by nearly a third to 350 by 1920. Chinese immigrants in the U.S. during this period witnessed extreme racism, legal battles, physical attacks and massacres, and a heavily skewed population. Where Utah and the United States in general possessed nearly one woman to every man, the Chinese ranged from 12 to 37 men for every one woman by the end of the 19th century. This heavily male population led to the widespread but erroneous belief that the few Chinese women in the United States were prostitutes or concubines, not members of families. It is from these few stories of Chinese women that Ah Yuen’s personal history emerges and becomes even more important. It is rare to see an individual Chinese woman in the historical records, let alone travel with her through her many years in the United States.

Christopher W. Merritt is an archaeologist with the Utah Division of State History, and has spent the last 15 years researching and writing on the Chinese experience in the United States.

Footnotes

[i] Information stems from the United States Federal Census Bureau between 1870 to 1930 in Utah Territory and Wyoming.

[ii] https://www.utahhumanities.org/stories/items/show/352

[iii] Ogden Standard Examiner January 13, 1939

[iv] Stewart Lone, “Daily Lives of Civilians in Wartime Asia”, Greenwood Press, 2007.

[v] “American Women and Immigration”, https://memory.loc.gov/ammem/awhhtml/awlaw3/immigration.html

[vi] Andrew Gyory. “Closing the Gate: Race, Politics, and the Chinese Exclusion Act”. University of North Carolina Press, 1998.