Additional Resources

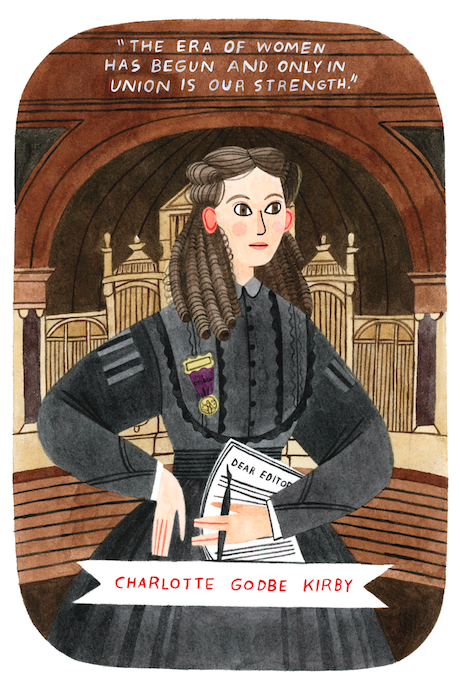

Charlotte Godbe Kirby,

Champion of "The Women's Era"

1836-1908

“The era of women has begun and only in union is our strength.”

by Tiffany Greene

Historical Research Consultant, Better Days

Educated, cultured, ambitious, outspoken, and bold, Charlotte Ives Cobb Godbe Kirby was an ardent women’s rights advocate and suffragist from the earliest days of the movement in Utah. Born in 1837 in Boston, Massachusetts, Charlotte and her mother Augusta Cobb moved to Nauvoo, Illinois in 1846, when Augusta left her husband to become a plural wife of Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints leader Brigham Young. Charlotte and Augusta migrated to Salt Lake City in 1848. They lived for a time in the Lion House, the home of Young and his wives, where Charlotte taught his other children in the family school and played piano for formal parties. Charlotte received “every advantage of education, culture and refinement which Utah afforded in those days.”[1] During the 1860’s, Charlotte traveled back to her native Boston with Augusta, where her mother introduced her to New England suffragists such as Lucy Stone, Paulina Wright Davis and Lucretia Mott.

Charlotte Godbe Kirby. Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

The year 1869 marked a new era of Charlotte’s life, a decade that would prove tumultuous, painful, exuberant, and thrilling for this ambitious woman. Charlotte became the fourth wife of William Godbe in January, with Brigham Young performing their marriage. William was an integral member of the New Movement, a splinter organization of the LDS Church that ultimately severed itself completely from the religion. For the first part of their marriage both William, Charlotte, and her sister wives Annie Thompson, Mary Hampton, and Rosina Colburn, were considered members of the LDS church. Shortly after their marriage, Charlotte and William traveled to the East Coast, where she continued her associations with leaders of the newly-formed American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA).

In 1871, Charlotte spoke on suffrage in Providence, Rhode Island, and also spoke to a group of 2,000 in Boston’s Tremont Temple at the request of Mary Livermore, an AWSA suffragist and acclaimed speaker. These speeches gave Charlotte the distinction of being the first Utah woman (and the first woman with voting rights) to speak to an audience of national suffragists. She was equally interested in connecting with the leaders of the more radical National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). Indeed, it was William Godbe and his wives who first invited and hosted Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony in Salt Lake City in the summer of 1871. The New Movement’s anti-polygamy stance caught the attention of NWSA leaders because they were anxious to claim solidarity with women’s suffrage in Utah without supporting polygamy. Charlotte’s efforts paid off when she was named as a Utah delegate to the National Woman Suffrage Association Educational Committee, making her the first Utahn to serve on a national suffrage committee.

In 1873, William Godbe separated from Charlotte and all his wives except for Annie, his first wife. Though her divorce from William wasn’t official until 1879, Charlotte spent most of that decade alone without apparent financial support. Now that she was even more distanced from polygamy, which she called a “painful experience” in later years, Charlotte gained some traction in both national suffrage organizations. Traveling extensively, she made appearances in Boston, New York, and Washington, D.C., as well as in several Utah towns, delivering her lecture titled “The Question of the Hour,” which was met with applause and accolades everywhere.

Ever assertive and bold, Charlotte said, “I think the idea a mistaken one that strong-minded women must of a necessity be unamiable.”[2] She spoke on the role that women should play in society for the betterment of all and hoped for a time when all women could unite regardless of religion or region. “The era of woman has begun and only in union is our strength. When earnest women can strike hands in fellowship and clasp them around the world in united effort, then…will men accept us as the power we have it in us to be.”[3] Speaking in Methodist churches, Mormon tabernacles and Baptist temples, it was her wish that “women could hold up the hands of any woman who is doing good work for their side.”[4]

In what became a constant theme throughout her life, Charlotte straddled the complicated dynamics of competing parties associated with the suffrage movement in Utah: the LDS church and the New Movement, and the leadership of the competing AWSA and NWSA organizations. Although she played an important part in all of these organizations, she was never fully accepted by any of them. Because the Godbes eventually rejected plural marriage, Charlotte had an ambiguous position as a plural wife who no longer supported the principle. This meant she was not accepted by many LDS suffrage leaders, most notably Emmeline B. Wells, as one of their own. Still, while William and his first three wives cut all ties to the LDS church, Charlotte tried in some ways to maintain her connection, corresponding with LDS church leaders John Taylor and Wilford Woodruff.

Charlotte Godbe Kirby. Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

At her core, Charlotte was a believer of equal rights, working to advance the cause of woman’s individual liberties, including but not limited to the right to vote, across all boundaries of religion or region. This expansive view was not always appreciated or accepted by female leaders of the LDS church. Charlotte went toe-to-toe with Emmeline B. Wells more than once over who could claim the right to speak for Utah women. But Charlotte remained undeterred. She visited London, again networking with leading female leaders there. She also contributed several editorial articles to the Woman’s Journal, the publication of the AWSA, as well as the Revolution, the publication of the NWSA.

Charlotte lived in Southern California for a time in the mid 1870s, where she met and befriended suffrage leader Caroline Severance. Charlotte appeared to be ubiquitous in suffrage organizations around the country. Obviously well connected and self promoting, Charlotte seemed to always be where the action was, regardless of what city she found herself in. She also actively promoted the temperance movement. The Moral Education Society in Washington D.C. claimed her as an honorary member and bragged “don’t let it ever be said that we don’t allow mormon women to join us.”[5]

Charlotte continued her involvement on the national scene into the 1880s. In 1881, she was a delegate to the NWSA convention in Washington D.C. where she spoke in Lincoln Hall. She stated, “It seems to be a time when women are called in to the field of action as never before; indeed, it is woman’s era. To stimulate in her the highest ambition to excel should be our chief aim.”[6] Charlotte also hosted several prominent national suffragists such as Mary Livermore when they traveled to or through Salt Lake City. When Congress revoked the voting rights of Utah women in 1887, Charlotte again inserted herself into local suffrage efforts and was appointed as the corresponding secretary of the Utah Woman Suffrage Association in 1889.

In 1884, Charlotte married successful miner John Kirby, who was her first cousin once removed. Though she never had any children of her own, she always applauded the importance of women taking care of their homes and families. In the 1890s, Charlotte and John adopted her grand-nephew Gordon, who lived with her until her death in 1908. Throughout her life, Charlotte unabashedly stood up and spoke out for the rights of all women. She astutely navigated competing local and national views, carving out a name for herself as a champion of women’s rights in the nineteenth century.

Tiffany Greene was a Historical Research Consultant for Better Days when she wrote this bio, then later worked as Education Director. She is a lifelong resident of Salt Lake City who loves learning about and sharing the lives of women past and present.

Footnotes

[1] Van Wagenen, Lola. Sister-Wives and Suffragists. Deseret Book Company, 2012.

[2] “Memorial.” Salt Lake Herald-Republican 11 April 1880, p.3

[3] “Views.” Salt Lake Herald-Republican 2 September 1883, p.11.

[4] Beeton, Beverly. A Feminist Among the Mormons:Charlotte Ives Cobb Godbe Kirby. Utah Historical Quarterly (Volume 59, Number 1, Winter 1991)

[5] “The Question of the Hour.” Salt Lake Herald-Republican 2 May 1879, p3.

[6] “Woman’s Suffrage” Territorial Enquirer 19 March 1881, p.2.