Additional Resources

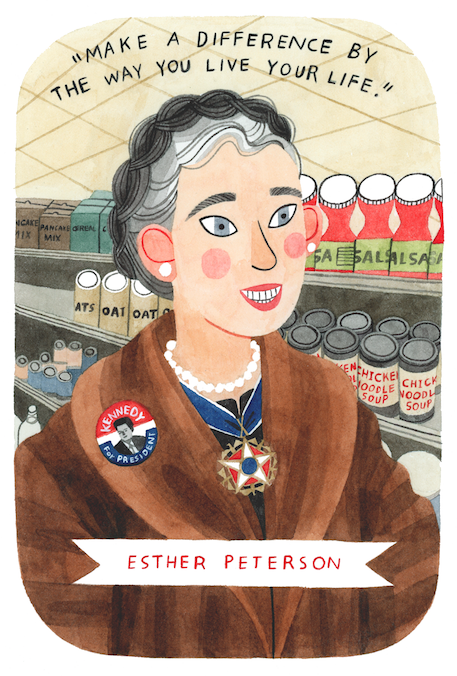

Esther Eggertsen Peterson,

Labor, Commerce, and Women’s Rights Advocate

1906-1997

“Make a difference by the way you live your life.”

by Naomi Watkins

Former Education Director, Better Days

Esther Eggertsen Peterson was a fierce advocate in the labor, commerce, and women’s rights movements who has been credited with over one hundred pieces of consumer legislation that affect us every time we purchase a can of food or a box of laundry detergent. She was a fighter and a unifier who was often referred to as “nanny to the world.”[1]

Born in Provo, Utah on December 9, 1906, Esther was the fifth of six children to Lars Eggertsen and Anagrethe Nielsen. Her father was superintendent of schools and her mother was a schoolteacher. Esther graduated from Brigham Young University in 1927 with a degree in physical education and accepted a position as a teacher at Branch Agricultural College in Cedar City, Utah. After teaching there for a year, she moved to New York City, earned a master’s degree from Teachers College at Columbia University in 1930, and held several teaching positions. While living and working in New York, she met Oliver Peterson. She “knew [she] loved him, but he was a socialist who drank coffee and smoked a pipe, and [she] was a conservative Mormon Republican from Utah.” They married in 1931, and she credited him with “the strength to work for change and to disturb the peace at times.”[2]

Esther Peterson in 1961. Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

In 1932, the couple moved to Boston, where Esther taught at The Windsor School, a prep school for wealthy girls, and volunteered at the YWCA teaching classes to garment workers. She noticed that no African American women attended the YWCA; they were barred from using the YWCA facilities and had to use another facility across town. Esther pointed out that this segregation was not only wrong, but it was also not in harmony with the organization’s statement of purpose that included equality and justice. The YWCA eventually integrated.

One class night at the YWCA, many of Esther’s students did not show because of an impending labor strike. Esther said, “I was raised thinking that [strikers] had bombs in their pockets and were communists.”[3] But her husband, Oliver, said, “Esther, don’t say that until you find out why.”[4] So together they went and talked with her students and their families. Esther found Eileen, a sixteen-year-old garment worker, her younger siblings, and her mother working at a table with a single light bulb hanging from above. The three-year-old was counting out bobby pins into piles of ten, and the older children were putting pins onto cardboard. Most of Esther’s students made house dresses for $1.32 per 12 dresses, but recently the dress company had changed the pocket design on the dresses from a square to a heart-shape, making it a more time-consuming task and thereby decreasing their wages. “A square is easy to sew but have you ever tried to sew around the curves of a heart?” Eileen asked. Esther realized these women and their families did not resemble her preconceived ideas; they were women working against incredible odds to support their families.

The next morning, when the garment workers went on strike Esther helped to organize and joined them on the picket line. She saw how by working together these women’s voices were powerful. This “Heartbreakers Strike” inspired Esther to become a “real labor activist,” she said. “I knew that the fathers of the kids at the prep school were the ones that were doing the exploiting. Their kids would come to school with chauffeurs in the morning, and [their fathers] couldn’t pay a minimum wage? Come on! I decided they had to have a voice, the working people. I felt the women were left out, they got the low end of everything.”[5] She then got involved with the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) and spent her summers teaching classes ranging from economics to poetry at the Summer School for Women Workers in Industry.

In 1938, Esther began working for the American Federation of Teachers as a paid organizer in the New England area. This same year she had the first of her eventual four children and discovered that the cost of child care exceeded her paid wages. She was earning $15 a week while paying a caregiver $20 a week to look after her child. She would later fight for legislation to strengthen the Fair Labor Standards Act, which established minimum wages and work hours, and she also worked to regulate overtime pay and child labor.

A few years later, in the summer of 1941, Esther returned to Utah to organize textile workers and lobby the Mode O’Day Company to convince them to sign a contract with the Garment Workers Union. When Esther was trying to buy advertising time at the local media station, KSL, her brother’s friend was surprised to see her there. He asked her, “What are you doing here disturbing the peace?” She was often referred to by her adversaries as “the most pernicious threat to advertising today”[6] due to her efforts to bring honesty and transparency to product advertisements.

In 1944, Esther and her family moved to Washington D.C. for her husband’s employment, and she became the first lobbyist for the National Labor Relations Board and the first female lobbyist for the the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Unions. At her first lobbyists’ meeting, all the men stood up when she walked in. Peterson didn’t want to be treated differently and announced, “Please don’t stand up for me. I don’t intend to stand up for you.”[7] She later said in an interview, “I love to use the word [lobbyist] because people’s ears usually prick up. Actually, one should understand that it’s an extremely essential part of our democratic process of government. I don’t know what senators would do, what people would do, without lobbyists. The main thing is to strengthen the lobby of the people who represent the people’s interests.”[8]

Four years later, her husband became a diplomat to Sweden, and Esther continued working on women’s issues when the family moved there. She wrote an anti-Communism pamphlet, “Women, It’s Your Fight, Too,” and helped organize the first International School for Working Women in Paris. When the family returned to Washington D.C. in 1957, Esther became the AFL-CIO’s first female lobbyist in its Industrial Union Department.

She worked on Senator John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign in 1960 in Utah, also having done so on President Franklin Roosevelt’s campaign in 1944. After Kennedy’s election, he nominated Esther to be the Assistant Secretary of Labor and the Director of the United States Women’s Bureau. As the highest-ranking woman in the Kennedy administration, she led the successful campaign to pass the Equal Pay Act of 1963, a law that established the principle of equal pay for equal work, regardless of gender.

Former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt (left) and Esther Peterson (right) serving on the President’s Commission on the Status of Women, January 1962. Courtesy of Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

Due to Esther’s influence, President Kennedy created the Presidential Commission on the Status of Women, and Esther selected former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt to chair the committee. Through her work on this panel, Esther hosted hearings across the country on the issues and problems facing working women. This process resulted in a bestselling report outlining the need and steps to improve child-care quality and availability, equal pay, and to end racial and gender workplace discrimination. This commission also laid the groundwork for the National Women’s Committee on Civil Rights to ensure that women of color’s voices were heard in the pursuit of civil rights. Esther always made sure she heard directly from the people most affected by legislation.

President John F. Kennedy receives the final report of the President’s Commission on the Status of Women, titled “American Women,” from Assistant Secretary of Labor for Labor Standards and Executive Vice Chairman of the Commission, Esther Peterson, on October 11, 1963. Courtesy of John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

After President Kennedy’s assassination in 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson nominated Esther to the newly-created position of Special Assistant for Consumer Affairs. She continued to fight for transparency in product advertising and created legislation requiring food labels that listed ingredients, nutritional value, price per unit, and expiration dates. Later, she served in a similar position under President Jimmy Carter, who awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1981 for her work in helping consumers make better informed purchasing decisions.

Esther Peterson in 1971. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Esther also worked as the Vice President for Consumer Affairs at Giant Food Corporation, was president of the National Consumers League, and became a TV and radio personality as she educated the public on the best nutritional buys. In 1993, President Bill Clinton named Esther as a UNESCO representative to the United Nations, and in this same year, she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. Esther was a member of the Woman’s National Democratic Club, and one of her prized possessions was a mink coat club members gave her that once belonged to Eleanor Roosevelt. Esther said, “I’ve always said when I think about [Eleanor Roosevelt], ‘What would she do in this situation?’ I’ve had some rather trying times at the UN in the work I’ve been doing. Then I think, ‘Esther, put her coat on and her arms around you, you’ll do the right thing!’”[9]

Esther died at the age of 91 in Washington, D.C. and is credited for championing many rights for workers, for consumers, and for women.

Dr. Naomi Watkins is an educational leader, certified forest therapy guide, and storyteller with over 20 years of experience in the K-12 and higher education systems. She wrote this bio as Education Director for Better Days and is currently the Secondary English Language Arts Specialist at the Utah State Board of Education.

Footnotes

[1] Salt Lake Tribune, 12 March 1995.

[2] Esther Peterson, “Roots and Wings,” The Alice Louse Reynolds Inaugural Lecture, Brigham Young University, September 22, 1988.

[3] “Esther Peterson: Advocate for Labor, Women, Consumers,” American Postal Workers Union, AFL-CIO.

[4] Interview with Esther Peterson, Library of Congress, December 16, 1992.

[5] Interview with Cokie Roberts, 1993. Retold in We Are Our Mother’s Daughters, Harper, 2010.

[6] The New York Times, 4 November 1969.

[7] “Esther Peterson: Advocate for Labor, Women, Consumers.”

[8] J. Y. Smith, “Consumers’ Advocate Esther Peterson Dies,” The Washington Post, 21 December 1997.

[9] Interview with Esther Peterson, Library of Congress, December 16, 1992.