Additional Resources

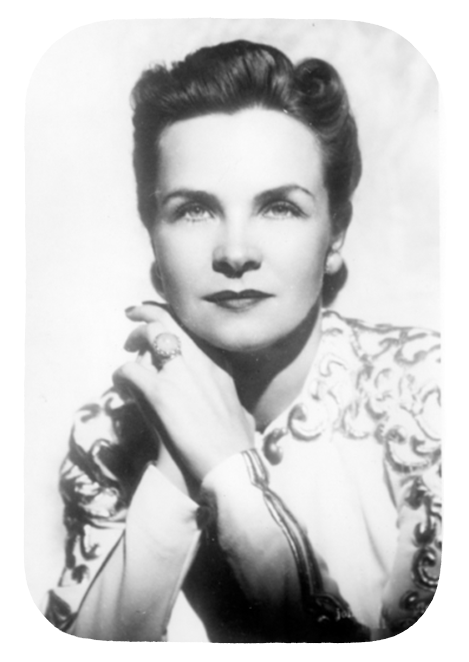

Helen Foster Snow,

Journalist and Nobel Peace Prize Nominee

1907-1997

“One can judge a civilization by the way it treats its women.”[1]

By John Murphy and Timothy Davis

Helen, before departing for China. BYU Special Collections.

As an intrepid journalist, author, and co-founder of China’s Gung Ho movement, Helen Foster Snow helped document revolutionary China during the 1930s. She was later nominated twice for the Nobel Peace Prize for her work in China. She wrote: “The nomination was not for any particular achievement, but for the potential that my ideas and world view hold for peace and progress in the world.”[2] The bridge of friendship Helen built with the Chinese people was so strong that there are many buildings named for her in China today.

Helen was born September 21, 1907 in Cedar City, Utah. As a young woman she moved to Salt Lake City and attended West High School. Upon graduating from high school, she enrolled at the University of Utah. However, bored with school and hoping to fulfill her childhood dream to become a famous writer and explore the world, she left the university and her job as an assistant to the secretary of the American Mining Congress. Having successfully passed the foreign service test for clerks and with the support of her father’s Stanford alumni friends and a recommendation letter from Utah Senator Reed Smoot, Helen departed from Seattle aboard the S.S. President Lincoln to take a clerkship in the U.S. Consulate in Shanghai. She arrived in September 1931.

Helen interviewing Shanghai mayor Wu Tieh-cheng (far right) after the Japanese invasion in 1932. BYU Special Collections.

Helen met the famous journalist Edgar Snow soon after her arrival. She and Edgar quickly became friends and over the course of the next year, Helen wrote a series of stories for American newspapers in which she documented the 1931 Shanghai floods and the 1932 Japanese invasion of the city. Despite the almost overwhelming human tragedy that she encountered, this was also a happy time for Helen. She and Edgar explored southern China together and after a yearlong courtship, they married on Christmas Day 1932.

Following an extended honeymoon where they explored Japan and Southeast Asia, Helen and Edgar relocated in 1933 to Beijing where Edgar taught journalism at Tsinghua University. Helen studied Chinese literature, history, and culture at Yenching and Tsinghua universities where she also developed close friendships with fellow Chinese students. Writing under the pseudonym “Nym Wales,” Helen continued to write articles for American newspapers and magazines on a variety of topics including the 1935 December Ninth Movement— an effort on the part of Chinese university students to mobilize in protest against Japanese militarism.

Helen in China. BYU Special Collections.

Over the course of the next two years, while living in Beijing, Helen traveled twice to Xi’an in northwest China. On her first trip in 1936, she interviewed “the Young Marshal” Zhang Xueliang, a Nationalist General who was committed to creating a United Front or alliance between the Chinese Nationalists and the Chinese Communists against Japanese aggression. On her second trip, in 1937, Helen again traveled to Xi’an, where she stayed briefly before making her way to Yan’an, the center of the Chinese Communist movement, to interview party leaders.

Helen with student activist Li Min at the Temple of Heaven in Peking, BYU Special Collections.

Breaking through the government-enforced news blackout, Helen was only the second foreign woman to enter the area and the eighth foreign journalist to have such access. She remained in Yan’an for approximately four months and interviewed prominent Chinese Communist leaders including Chairman Mao Zedong, Vice-Chairman Zhou Enlai, and Commander of the Red Army, Zhu De. Helen also interviewed students, educators, workers, women revolutionaries, soldiers, writers, actors, and musicians. Many of these interviews were incorporated into a series of newspaper and magazine articles and were later published as a selection of biographical profiles in her book titled Red Dust.

In the fall of 1937, Helen left Yan’an and returned to Beijing. Several months later, she traveled to Shanghai, where she hoped to recover from exhaustion and ill health. Upon her arrival in Shanghai, she and Edgar found themselves in a city now largely occupied by the Japanese Imperial Army. Even though she found herself living in a city occupied by a foreign enemy, Helen managed to complete her classic work, Inside Red China, in September 1938.

Helen with Edgar (l) and Rewi Alley (r). BYU Special Collections.

Together with Edgar and family friends Rewi Alley and Ida Pruitt, Helen established the Chinese Industrial Cooperative Association (INDUSCO). The Cooperative Association, which came to be known as the Gung Ho movement, was created to assist Chinese refugees and others who were dislocated and otherwise impoverished by the war, as well as to develop the Chinese economy in the interior of the country away from Japanese-occupied coastal areas.

Although Helen and Edgar had hoped to remain in China, by late 1938, the situation for both of them had become untenable. Both Helen and Edgar were sick, and the danger posed by the invading Japanese Imperial Army had increased dramatically. To escape the Japanese forces, Helen and Edgar traveled first to Hong Kong and then the Philippines, where they lived for the next two years. In the Philippines, Helen worked tirelessly to further develop and promote INDUSCO. She solicited donations to fund the Chinese cooperatives, worked closely with colleagues in China to establish additional Gung Ho cooperatives, and tirelessly promoted the Cooperative movement in the United States. In 1940, Helen also published her account of the Cooperative movement, China Builds for Democracy: A Story of Cooperative Industry.”

BYU Special Collections.

In order to “escape from the East before Japan made us prisoners of war,”[3] and with the recommendation of the United States government who had encouraged all American women and children to evacuate East Asia, Helen left for America in December 1940. Upon her arrival in the United States, Helen lived in California where she awaited Edgar’s arrival. Reunited in February 1941, Helen and Edgar spent time in California, traveled to Arizona and Utah, and met with U.S. government officials in Washington, D.C., including First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, with whom they discussed the INDUSCO program. Helen and Edgar eventually purchased a home in Madison, Connecticut. Following the end of World War II, they separated and formally divorced in 1949.

Helen’s statue in Main Street Park, Cedar City. Chinese dignitaries brought the statue to Utah in 2009.

Helen remained in her Connecticut home where she continued to research and write. She traveled widely and renewed friendships with her Chinese friends in the 1970s, when she welcomed them to her Connecticut home. Helen returned to China for the first time in 1972 and for the second time in 1978. She completed her autobiography, My China Years, in 1984. In 1996, China bestowed one of its highest honors for a foreigner by naming Helen a Friendship Ambassador. Helen died in Connecticut at the age of ninety on January 11, 1997. An official Chinese memorial service took place in the Great Hall of the People on Tiananmen Square in Beijing, a rare honor and testament to the impact this Utah woman had on an entire nation.

John Murphy is the Curator for 19th and 20th manuscripts at the Harold B. Lee Library, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University.

Timothy Davis is the Asian Studies Librarian at the Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

[1] Nym Wales [Helen Foster Snow], Women in Modern China (Paris: The Hague, 1967) 223.

[2] Helen Foster Snow, My China Years: A Memoir (New York: Morrow, 1984) 329.

[3] Helen Foster Snow, My China Years, 323.