Lucille Bankhead,

Defender of African-American Rights

1902-1994

“I’m a woman…I’m going to say just what I want to say.”

By Tarienne Mitchell

Mary Lucille Perkins Bankhead was a descendant of African-American Mormon pioneer Green Flake and was related through marriage to another Black Mormon pioneer, Jane Manning James. Lucille, as she was called, spent all her life in the Salt Lake Valley. Lucille’s father was a cowboy and farmer who grew peaches and black currants on land that he received through the Homestead Act. Lucille helped her parents work on the farm, do housework, and take care of her younger siblings.

In 1922, Lucille married Thomas LeRoy “Roy” Bankhead, a descendent of Nathaniel Bankhead, a slave who also traveled across the plains with members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Roy was not active in the Church, but he supported his wife by driving her to Church meetings and activities. The Bankheads had eight children. Along with being a wife and a mother and serving in her church, Bankhead served as a secretary for the Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

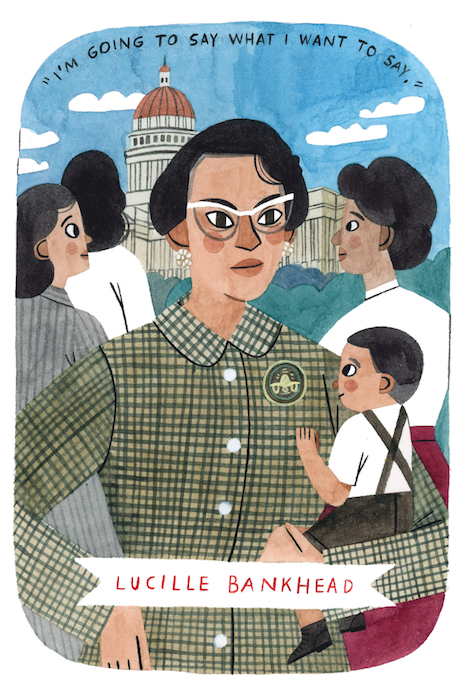

(left to right) Martha J. Perkins Howell, Lucille Bankhead, Ruth Jackson, Juanita Spillman (child). Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

In 1939, state representative Sheldon R. Brewster began a campaign for a law that, if passed, would force black Salt Lake City residents to move out of their current homes and into a segregated designated area to be known as the “black district.” This senator even hired an African American man to go door to door to help gain support for the law. When Lucille heard about the push for this proposed law, she felt the need to fight for her rights. She recounted, “Well, at that time, I belonged to the Camilla Art and Craft Club, and when several other women and I discussed this, we thought it was a ridiculous idea.” “…we took the baby and we took a lunch and we took two or three of the women that belonged to Camilla Art Craft Club. And Mrs. Lagroan [Leggroan]* and I drove, and we drove this horse and wagon up.”

“We sat up there in the legislature all day. And of course, we told them what we wanted and that we was not going to move – that what we really wanted was our land and we had no intention of selling. That was the first time we ever been up to the legislature, but we just sat there waiting to be heard.” “And we stayed till we knew the legislature realized what they had to do. Then we went home. I guess the people at the legislature was glad to see us go. I have to laugh about it now.”

Because of the efforts of Lucille Bankhead, Mrs. Leggroan, the ladies from the Camilla Art Craft Club, and others, the law didn’t receive the votes it needed to pass and black Utahns were able to stay in their homes. Of this Bankhead had to say, “If I don’t like what you’re doing, I think I’m right, I’m going to open my mouth. I’m going to talk about it. And somebody’s going to hear. And if they don’t like it, why that’s just too bad… I’m a woman, don’t make no difference what color my skin is. I bleed just like you do. And I’m going to say just what I want to say.”

Lucille and Roy Bankhead.

When the Genesis Group, a support group created by the LDS Church for black members, formed in October 1971, Lucille was called to be its first Relief Society president. She often remarked that she found her calling supporting her fellow black women in the Church challenging and recalled crying a lot. When asked what she thought of the ban prohibiting black members to hold certain positions of leadership or perform certain rites in the LDS temples (often referred to as the priesthood ban), Lucille said during in an interview, “There is one verse in the Bible that the Lord is no respecter of persons and I’ve always believed that.” After the revelation on the priesthood in 1978, Lucille served as proxy for the temple endowment of her ancestor Jane Manning James.

In 1987, Lucille was honored for her strength and leadership at the first annual Ebony Rose Black History Conference held in Salt Lake City, Utah, where she was a featured speaker. She passed away in 1994 and was buried in the Elysian Gardens Cemetery next to her husband.

* In one of the oral history interviews, Lucille says that Mrs. Leggroan was a neighbor of hers. According to the 1940’s US census Mrs. Leggroan is one of three Leggroan women living near the Bankhead family. Their names are Catherine Leggroan, Alice Leggroan, and Eleanor Leggroan. For more information see FamilySearch source information.

Tarienne Mitchell is an archivist at the LDS Church History Library.