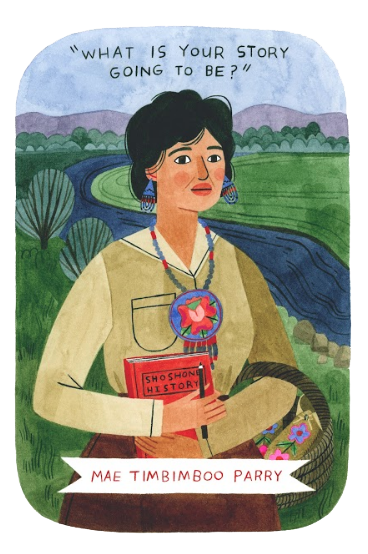

Mae Timbimboo Parry,

Historian and Matriarch of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone

1919-2007

“What is your story going to be?”

By Darren Parry

For as long as I can remember, my Native American culture has always been something I was proud of, and that I wanted to share with the world. That feeling was written upon my mind and soul through my loving grandmother, Mae Timbimboo Parry. I spent almost every day of my youth at her side. She was always making buckskin moccasins and gloves and other items that she would sell or often give away, even to complete strangers. Her mastered skills were so carefully displayed, and each bead was threaded for someone she loved. She was quiet and thoughtful, but she had an unbreakable spirit. The deep creases in her skin told of a life lived hard, a life of giving, a life of loving, and a life of caring. She was and still is my hero.

Mae Timbimboo Parry, courtesy of Darren Parry.

My grandmother was our story teller, a calling that would one day be mine. She was our tribal historian. This title is important to my Native people because it is the job of the tribal historian to carry on our traditions and histories that have been passed down for generations. I would sit at her feet and listen to stories, just as she had done with her own grandparents. It was important to her that I understood all of the details. This was the only way that those important events would become memory and then be passed down to future generations.

Mae was born to Moroni Timbimboo and Amy Hewchoo Timbimboo on May 15, 1919 in Washakie, Utah. She went through the boarding school system of the 1920s, which was designed to assimilate Native Americans into the Euro-American culture. Their creed was “kill the Indian to save the child.” If she spoke her language or referred to her people or culture in any way, she was punished. This was not easy on a young Shoshone girl. On one occasion Mae’s teacher at the Washakie Day School stood her on a chair and said, “Mae, you are going to turn out to be just like these other children, sitting in the dirt and being useless for the rest of your life.” I want to believe that this gave her an even greater incentive to be successful, not only in school, but in life. She returned home and continued her education at Bear River High School and then LDS Business College, where she earned her degree in English. She married Grant Parry in 1939 and they made their home in Clearfield, Utah.

Mae Timbimboo Parry, Brigham City Museum of Art & History.

While she was in high school, Mae did something that has literally saved our culture. She began writing down all the stories that she had heard from her tribal elders, and her grandfather Da-boo-zee, who was 12 years old at the time of the Bear River Massacre. She impacted the way the history of the massacre was recorded and she set the record straight in many ways. But it was also important to her that everyone’s point of view was heard and respected. Everyone has a story that is worthy to be told. She would often ask me, “What is your story going to be?”

As our tribal historian and keeper of the oral stories, my grandmother was of some importance. She had been to Washington, D.C. more times than I could count. There, she met with Senators and Representatives and other government officials. She served as a representative on the White House Council for Indian Tribal Affairs, working with other Native American leaders to coordinate federal programs and resources for tribes. She was also instrumental in helping Utah develop its Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, to return Native American artifacts and human remains to the indigenous tribes they belonged to. She was recognized with the Utah Women’s Achievement Award.

In 1986 Mae won what she considered the best award of all—she was named “Utah Honorary Mother of the Year.” Not only was she the mother to her own six children, she was the mother to her tribal family. She was our tribe’s matriarch, instilling in them a love of God, a love of education and a love for their people. Even after she was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, she led and taught and loved with the same passion that she always had. Her shaking, the effects of Parkinson’s, made it impossible for her to make those prized gloves or moccasins as she used to, but her mind was sharp and she never did quit teaching.

Mae Timbimboo Parry, courtesy of grandson Darren Parry.

The story of my people, the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation, from our perspective, is a story of faith, a story of forgiveness, and a story about a group of people who overcame great tragedy and loss. The massacre at Boa Ogoi, where hundreds of my people were killed on January 29, 1863, was the largest massacre of Native Americans by federal troops in the history of the United States. There were many ramifications. It changed how the U.S. Army dealt with other Native American tribes in the future. It also altered the lives of a small band of people who only wanted to be left alone, so they could live a life that their people had lived for thousands of years. Still, the Bear River Massacre does not define us today. It has made us stronger. We have used those stories and tragedies to inspire and motivate us to be better people and a better nation.

My grandmother played a crucial role in sharing this history and our Shoshone culture. She always spoke from her heart and was as comfortable speaking to young children as she was to great leaders. She would bring old stories to life that would captivate any audience. I have learned that people forget facts and figures about history, but they will never forget the feelings they felt when they hear a story. This is what was different about my grandmother. She was a story teller. She was an icon to her people, and a treasure to me. Mae passed away in 2007, and I often wonder what she would think about where her people are today. It was so important to her that the story of her people be told and be heard from our unique perspective. Because of her, we now have the opportunity to share that story with the world.