Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon,

First Female State Senator

1857-1932

“All men and women are created free and equal.”

By Rebekah Clark

Historical Research Associate, Better Days 2020

A pioneer in many respects, Martha “Mattie” Hughes Cannon (1857-1932) blazed trails for women as a skilled physician, ardent suffragist, progressive public health reformer, and most notably, the first female state senator in the United States.

Martha Hughes Cannon in 1880. Photo courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

Born in Wales, United Kingdom, young Martha immigrated with her family to Utah Territory to join the Latter-day Saints in 1861. Deeply impacted by the deaths of her baby sister and father, bright and independent Martha aspired to be a medical doctor at a time when women rarely even went to college. In response to Brigham Young’s encouragement for women to enter the medical field, she enrolled in the University of Deseret (now the University of Utah) at age sixteen to fulfill the pre-med requirements. While earning her chemistry degree, she saved money for medical school by working as a typesetter for the Deseret News and then the Woman’s Exponent, where she became immersed in the women’s rights movement. She earned her medical degree from the University of Michigan in 1880 and a degree in pharmaceuticals at the University of Pennsylvania in 1882, where she was the only female student in her program. She displayed exceptional public speaking skills and simultaneously earned a degree from the National School of Elocution and Oratory in Philadelphia, giving her four degrees by the time she was twenty-five.

Martha Hughes Cannon in 1887. Photo courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

Back home in Salt Lake City, Martha set up a private medical practice and became the resident physician at the woman-run Deseret Hospital. In 1884, during the height of the national anti-polygamy movement, she secretly married prominent Latter-day Saint church leader Angus M. Cannon and became the fourth of his six polygamous wives. As polygamy prosecutions intensified, Martha moved to England in 1886 with her infant daughter Elizabeth. She lived there in exile for more than a year to avoid incriminating her husband or being forced to testify against her obstetrics patients. Angus ended up being convicted of cohabitation anyway and served six months in prison. Letters between Martha and Angus illustrate her deep love for him, her faith in her religion, and her strong-willed independence, but they also reveal the loneliness, jealousy, and depression she battled while in exile. She and Elizabeth returned to Utah in 1888, where Martha resumed her private medical practice and established a nursing school. Two years later, Martha gave birth to her son James.

While Martha was living in Europe, federal anti-polygamy legislation in 1887 had repealed the voting rights that Utah women had exercised for seventeen years. Upon her return, she quickly became a leader in Utah’s burgeoning suffrage movement. Shortly after the formation of the Utah Woman Suffrage Association in 1889, Martha delivered a “well written address” at a large territorial suffrage meeting held in the Assembly Hall on Temple Square, where she argued: “No privileged class either of sex, wealth, or descent should be allowed to arise or exist; all persons should have the same legal right to be the equal of every other, if they can.”

Martha Hughes Cannon in 1892. Photo courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

She was a featured speaker at the Women’s Congress of the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, prompting the Chicago Record to observe: “Mrs. Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon. . .is considered one of the brightest exponents of woman’s cause in the United States.” At a territorial suffrage meeting in Salt Lake City in 1894, she again strongly advocated for women’s rights based on equality, arguing that “one of the principal reasons why women should vote—is that all men and women are created free and equal.” In 1898, she testified before a United States legislative committee on the success of Utah women’s suffrage and also spoke at the Seneca Falls 50th celebration in Washington, D.C., asserting: “The story of the struggle for woman’s suffrage in Utah is the story of all efforts for the advancement and betterment of humanity.”

When the Utah constitutional convention approved including women’s suffrage in the new state constitution in 1895, Martha was the first woman in Salt Lake City to register to vote. The territorial court, however, ultimately determined that women could not vote in that pre-statehood election to ratify the constitution and elect the new state’s first legislature. The next year, in the first Utah election that permitted women to vote and run for office, Martha ran as a Democrat in an at-large election for one of five state senate positions. Her husband and Emmeline B. Wells were also on the ballot as Republican candidates. The Democratic-leaning Salt Lake Herald endorsed Martha rather than her Republican husband, stating that she was “the better man of the two.” When the election results were counted, the Democrats swept the election. Martha’s victory garnered national attention not only because she was the first woman elected to a state senate but also because she ran against and defeated her own husband.

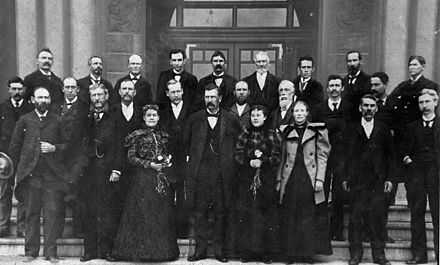

Cannon, on left front center, with the state senate (and secretaries) in 1897. Photo courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

Martha continued to practice medicine while she served one four-year term with the otherwise all-male Utah Senate in the Salt Lake City and County Building. As a Utah state senator, she authored several successful legislative bills that revolutionized public health and sanitation in Utah. She also sponsored a pure food law and a law regulating working conditions for women and girls, spearheaded funding for the education of speech-and-hearing-impaired students, and helped establish Utah’s first state board of health. She joined forces with Representative Alice Merrill Horne, the only other woman serving in the state legislature during the 1899-1900 term, to achieve their most important legislative victories. During debates over both Cannon’s public health bill and Horne’s art bill, they secured success by scattering yellow flowers on the desks of male legislators as a symbol of women’s suffrage and the influence they wielded among female voters.

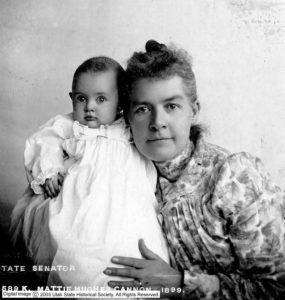

Martha Hughes Cannon with daughter, Gwendolyn, in 1899. Photo courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

In April 1899, while she was still in office, Martha once again made headlines by giving birth to her third child, Gwendolyn. Occurring well after the 1890 Manifesto that officially ended Church-sanctioned polygamy, Gwendolyn’s birth was cited as evidence of the continuation of polygamy in Utah. In the wake of resurgent anti-polygamy sentiment, sparked by the concurrent disputed election of polygamist B. H. Roberts to the U.S. Congress, Martha’s husband Angus was arrested, convicted, and fined for unlawful cohabitation. Newspaper reports on the trial emphasized Martha’s prominence as the first female state senator. Perhaps because of this controversy, Martha chose not to run for another term in 1900. She moved to California with her children in 1904, worked at the University of California Graves Clinic, and became the vice-president of the American Congress for Tuberculosis. Martha passed away in Los Angeles in 1932.

Martha Hughes Cannon in 1917. Photo courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

Martha Hughes Cannon called for a wider sphere for women, explaining: “You give me a woman who thinks about something besides cook stoves and wash tubs and baby flannels, and I’ll show you, nine times out of ten, a successful mother.” She struck an often difficult balance between the demands of motherhood to her three children and her passion for public service and health. Expressing a philosophy that defined her approach to life, she urged: “[L]et us not waste our talents in the cauldron of modern nothingness, but strive to become women of intellect, and endeavor to do some little good while we live in this protracted gleam called life.”

Martha’s statue is going to Washington! The Utah legislature voted in 2018 to send a statue of Dr. Cannon to National Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol. The completed statue by Ben Hammond is in the Utah State Capitol until Martha’s installation can be scheduled (thanks, COVID). In the meantime, there’s a traveling exhibit and free teacher toolkits sharing Martha’s story statewide! Click here to see the schedule or request your free toolkit.

Click here for our collection of primary sources about Martha’s life and work, curated for the classroom.

Rebekah Clark holds a law degree from J. Reuben Clark Law School and a bachelor’s degree in American History and Literature from Harvard University, where she wrote her honors thesis on Utah’s participation in the national women’s suffrage movement. She is a member of the Mormon Women’s History Initiative Team and the Historical Research Associate for Better Days 2020.

Footnotes

[1] For published materials relating to Martha Hughes Cannon, see Jonathan A. Stapley and Constance L. Lieber, “Do Some Little Good While We Live,” Women of Faith in the Latter Days, vol. 3, eds. Richard E. Turley Jr. and Brittany A. Chapman (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2014); Letters from Exile: The Correspondence of Martha Hughes Cannon and Angus M. Cannon, 1886-1888, eds. Constance L. Lieber and John Sillito, (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1989); Mari Graña, Pioneer, Polygamist, Politician: The Life of Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon (Guilford, CT: TwoDot, 2009).

[2] “Woman Suffrage Meeting,” 17 Woman’s Exponent (May 15, 1889), 190.

[3] “Woman’s Great Forum,” Chicago Record, May 15, 1893, 1; “Utah Women in Chicago,” Woman’s Exponent 21, no. 24 (June 15, 1893): 179.

[4] Martha Hughes Cannon, “A Woman’s Assembly,” Woman’s Exponent 22, no. 15 (April 1, 1894): 114.

[5] Martha Hughes Cannon, “Woman Suffrage in Utah,” February 15, 1898, U.S. House of Representatives Committee on the Judiciary Hearing on House Joint Resolution 68, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

[6] Salt Lake Herald-Republican, October 31, 1896, p. 4.

[7] “Senator Cannon’s Baby,” Ogden Daily Standard, April 22, 1899; “Angus M. Cannon Under Arrest,” Salt Lake Tribune, July 9, 1899; “Angus Cannon Under Arrest,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, July 9, 1899.

[8] Annie Laurie Black, “Our Woman Senator,” San Francisco Examiner, November 8, 1896. Reprinted in the Salt Lake Herald, November 11, 1896.

[9] Martha Hughes Cannon to Barbara Replogle, May 1, 1885, quoted in Stapley and Lieber, “Do Some Little Good While We Live,” 17.