Additional Resources

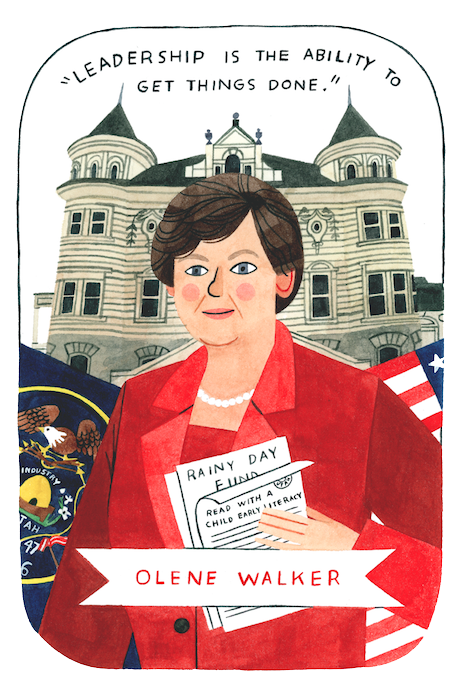

Governor Olene Walker,

Utah's First (and only) Female Governor

1930–2015

“Leadership is the ability to get things done.”

By Nena Slighting and Lisa Carricaburu

“I’ve always thought leadership was the ability to get things done. I look and say, ‘These are the things we need to do. Let’s get them done.” [1] Olene S. Walker’s straightforward definition of leadership speaks volumes about the remarkable woman whose steady path to power led her at age 72 to serve as Utah’s first woman governor, from November 5, 2003, to January 3, 2005.

Never in 25 years of public service did Olene S. Walker make excuses or balk at obstacles. She set an ambitious agenda for her term as governor, and in just 14 months accomplished many of the goals she had set forth in 14 far-reaching initiatives. Governor Walker established statewide programs to encourage early literacy skills and help children in foster care transition to adulthood. She acted to protect watershed areas in all Utah counties, and made progress toward reforming Utah’s tax code, among other accomplishments.

Governor Olene Walker. Courtesy of Nena Slighting.

Governor Walker “is a shrewd politician, a woman determined to make a difference with the power she has earned,” The Salt Lake Tribune wrote in naming her its 2003 Utahn of the Year. “She is a mother, grandmother, an educator, and a businesswoman as well, with a palpable feel for the people who live here and for their needs and aspirations. She seems the kind of person our forefathers had in mind when they aspired to create a government ‘of the people, by the people, and for the people.” [2]

Olene Smith was born on November 15, 1930, the second of five children of Thomas O. Smith and Nina Hadley Smith. Both parents were educators in addition to operating a 100-acre farm, and her father was Ogden School District superintendent for 25 years. The future governor’s interest in leadership surfaced early. Olene recalled lying on the grass and gazing at the stars one summer night with friends who were talking about what they wanted to be when they grew up. While the other girls spoke of being wives and mothers, Walker told them matter-of-factly: “I want to be president.”

Olene was an outgoing youth whom adults regarded as influential to her peers. She earned her first elected office in junior high school and went on to hold numerous leadership positions as a teenager in school clubs and her church. She loved sports and also participated in both debate and extemporaneous speaking. Those latter pursuits earned her a debate scholarship to Weber College. After her first year, Olene transferred to Brigham Young University, where she participated in student government while majoring in political science and earning a certificate to teach high school.

Olene’s academic achievements had just begun. After graduating from BYU in 1953, she received a scholarship to study political science at Stanford University, where she earned her master’s degree in 1954. She considered accepting a two-year Rotary fellowship to Italy but decided instead to marry Myron Walker that same year. The couple moved to Boston so he could pursue a graduate degree at Harvard University.

While in Boston, Olene worked in new accounts at Polaroid Corporation, but she credits the launch of her career to the countless school, community, and church leadership roles she embraced while raising her seven children. Even though her family moved 10 times in 13 years before settling in Salt Lake City, Olene served as PTA president of every school her children attended. Olene’s volunteer work led to part-time paid work as an education consultant developing curriculum and later evaluating federal Title III literacy and language acquisition programs. She ended up running a federal program for the Salt Lake City School District and later founded and operated the Salt Lake Education Foundation.

In 1976, Olene began pursuing a doctorate in educational administration at the University of Utah while continuing to work in education and caring for her family. She accomplished this feat by setting aside the hours of 11 p.m. to 3 a.m. each day to study, research, and write her dissertation. This achievement is even more remarkable considering that Olene was first elected to the Utah Legislature while finishing her doctoral degree. Walker served eight years in the Legislature from 1981 to 1989, one of only seven women among 104 state lawmakers during that time.

At a time when few women served in the Legislature and none held a leadership role, Walker ascended to several top positions. In her second term, she was named chairwoman of the powerful Appropriations Committee. Her peers elected her assistant majority whip in her third term and majority whip in her fourth term. “I learned quickly that if you wanted to get things done, you needed to be in leadership,” Walker said. Walker shepherded dozens of bills to passage, but few would have more lasting impact than the creation of Utah’s Rainy-Day Fund to protect state programs during times of economic downturn. Olene considered it her most important legislative accomplishment.

After serving four terms in the Utah House, Olene became Utah’s community development director in 1989. Her tireless advocacy for affordable housing gained traction during the two years she spent in that position. Today, the Olene Walker Housing Loan Fund continues to foster development of affordable housing for low-income Utahns.

Olene was considering running for Congress when gubernatorial candidate Mike Leavitt asked her to be his running mate for Lieutenant Governor. Olene told him that if they were to be elected, “I wouldn’t just want to cut ribbons and hand out trophies. He said, ‘Fine. That will work because I know people trust you.’” They won the election, and Olene became Utah’s first woman lieutenant governor in 1993. During 11 years in the office, she made good on her goal to be more than a figurehead.

As chairwoman of the state’s Health Policy Commission, Olene oversaw creation of the Children’s Health Insurance Program and other critical health policy. Walker also was chairwoman of Utah’s Workforce Task Force, whose work led to the consolidation of welfare, employment, and other programs managed by different state departments into the Utah Department of Workforce Services.

Olene Walker with school kids at the Olympic Torch Celebration, 2002. Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

Olene was also elected chairwoman of the National Conference of Lieutenant Governors and was the first lieutenant governor elected president of the National Association of Secretaries of State.

“Olene Walker’s leadership style throughout her public career was characterized by even-handed, public-spirited common sense,” Governor Leavitt said. “She isn’t an ideologue, but it would be a mistake to confuse that with a lack of clarity in her views. Her focus has always been the betterment of Utah, even if that meant political independence … She will always be seen as trailblazer, not just for women, but for all public servants.” [3]

Governor Leavitt’s selection by President George W. Bush to head the Environmental Protection Agency led to Olene’s swearing in as Utah governor on November 5, 2003. “I was excited because I could do what I wanted to without getting anyone’s permission,” she said. Governor Walker didn’t waste a minute in carrying out her ambitious plans. Some of her actions, such as her veto of a public school voucher bill, angered conservative members of the Republican Party. She left office in 2005 after failing to earn her party’s support to run for a second term during the Utah State GOP Convention, yet she remains one of Utah’s most popular governors ever, having finished her term with an 87 percent approval rating.

After two years of volunteer church service with her husband in New York City, Olene continued her active involvement in numerous political and community organizations in Utah, including Count My Vote, an initiative to change Utah’s caucus system for selecting candidates, the Utah Debate Commission, and Real Women Run, which encourages Utah women to seek elected office. In 2012, she established the Walker Institute of Politics and Public Service at Weber State University to inspire the future of political engagement and leadership in Utah. Despite her many accomplishments and interests, she considered her family her greatest achievement, including 7 children, 25 grandchildren and 34 great grandchildren. She had an amazing capacity to care for those around her.

Olene said, “Look at your life and ask yourself: What do I need to do for my children? What do I need to do for my neighborhood, my community, or my church, regardless of which church I belong to? There are many worthwhile things for people to do. They just need to do them, not just talk about them. Do little things that lead to big things.”

Nena Slighting is Olene Walker’s daughter.

Footnotes

1 Madsen, “Developing Leadership: Learning from the Experiences of Women Governors,” University Press of America (2009): 235

2 “Utahn of the Year: 2003: Olene Walker, Utah Governor,” The Salt Lake Tribune (December 29, 2006):1

3 Ghazi Askar, “Olene Walker: Legacy Without an Heir,” Deseret News (July 10, 2011)