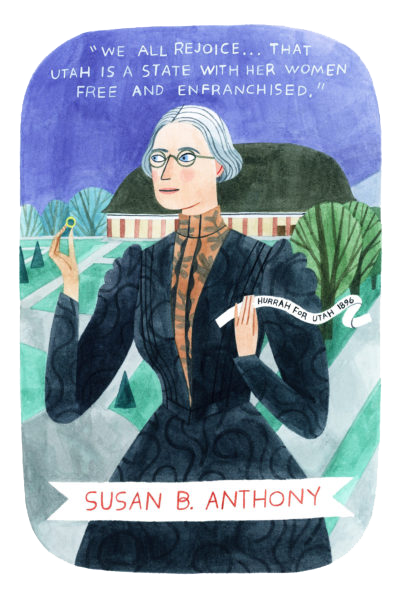

Susan B. Anthony,

A Champion of Utah

1820 – 1906

“Hurrah for Utah!”

By Barbara Jones Brown

Like many American suffragists, Susan Brownell Anthony (1820 – 1906) began her activism by working to abolish slavery. Raised in upstate New York in the Quaker tradition, she became passionate about social equality and started collecting anti-slavery petitions when she was just sixteen. In 1856 she became New York’s agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society. She also worked with Harriet Tubman in the Underground Railroad. Tubman later joined Anthony in the women’s rights movement.

Twenty-eight-year-old Susan B. Anthony in 1848, the year her soon-to-be friend, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, started the women’s rights movement, in Seneca Falls, New York.

In 1851, Anthony met Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who three years earlier had organized the nation’s first women’s rights convention in her hometown of Seneca Falls, New York. The two women became fast friends and co-workers, spending their lives fighting for the women’s ballot that they themselves would not live long enough to cast. In 1869 they organized the National Woman Suffrage Association and served as its president and vice-president.

Anthony is arguably America’s best-known suffragist, but her ties to Utah are lesser known. The year after Utah women became the first in the modern nation to exercise voting rights (on February 14, 1870), Anthony and Stanton visited the territory, congratulating Utah for granting women the ballot. There they held a five-hour meeting with three hundred local women in the Old Tabernacle, where the Salt Lake Assembly Hall now stands.

Even though she opposed the Mormons’ practice of polygamy, Anthony staunchly supported Mormon women’s voting rights. Though it cost her politically, she offered her friendship to polygamous suffragists and invited them to participate in national suffrage conventions when others turned their backs on them. Anthony formed an enduring friendship with Utah’s leading suffragist, Emmeline B. Wells.

To show their appreciation, women of Utah sent Anthony a bolt of black silk produced in their woman-owned silk industry. Anthony had a cherished dress made from the silk, which today is displayed in her bedroom at the National Susan B. Anthony Museum & House in Rochester, New York.

Susan B. Anthony’s bedroom and black dress made from Utah women’s silk. Photo courtesy of National Susan B. Anthony Museum and House

After Congress revoked the voting rights of all Utah women through the Edmunds-Tucker Act of 1887, Anthony mentored Utah suffragists on how to win those rights back. As Utah delegates prepared to submit a constitution for their 1895 application for statehood, Anthony urged Utah suffragists to ensure that a clause guaranteeing suffrage, regardless of gender, be included in the constitution. “Now in the formative period of your constitution is the time to establish justice and equality to all the people,” she wrote Emmeline Wells. “That adjective ‘male’ once admitted into your organic law, will remain there. Don’t be cajoled into believing otherwise.” [1]

Led by Wells, women throughout Utah lobbied the all-male delegates to include in the state constitution a clause guaranteeing women’s rights to vote and hold public office. After Wells telegraphed Anthony to announce that goal was realized, Anthony quickly replied, “Hurrah for Utah, No. 3 State—that establishes a genuine ‘Republican Form of Government.’” [2] When Utah officially became a state on January 4, 1896, it also became the third state, after Wyoming and Colorado, to grant woman suffrage.

Just as she had done after Utah Territory granted women the vote in 1870, Anthony personally congratulated Utah again in 1895, speaking to a crowd of 6,000 in the Salt Lake Tabernacle during the Rocky Mountain suffrage convention. Utah suffragists Emily and Franklin S. Richards opened their Avenues home in Salt Lake City for a reception for Anthony, attended by hundreds.

Susan B. Anthony (seated at center) met with Western suffragists, including Utahns Martha Hughes Cannon (standing, far left), Electa Bullock (seated, far left), Sarah M. Kimball (standing directly behind Anthony), Emmeline B. Wells (standing to Anthony’s left) and Zina D. H. Young, (seated directly left of Wells), at the 1895 Rocky Mountain woman suffrage convention in Salt Lake City. Photo courtesy of Utah State Historical Society

In 1906, at the age of eighty-six, Anthony died from pneumonia. On the day of her death, she had one of her gold rings sent to Emmeline Wells in Utah, a symbol of her friendship and legacy. Anthony was so beloved in Utah that upon her death, a memorial service was held for her in the Salt Lake Tabernacle, whose interior had twice reverberated with the strength of her voice. Though she died fourteen years before the 19th Amendment passed, Anthony left an indelible imprint on the state and on the nation. “Failure is impossible,” was her best-known motto, and she was right.

Barbara Jones Brown is the Executive Director of the Mormon History Association.

Footnotes

[1] Susan B. Anthony’s Letter,” Woman’s Exponent 23 (August 1-15, 1894): 169.

[2] “Equal Suffrage in the Constitution,” Woman’s Exponent 23 (May 1, 1895); 260.