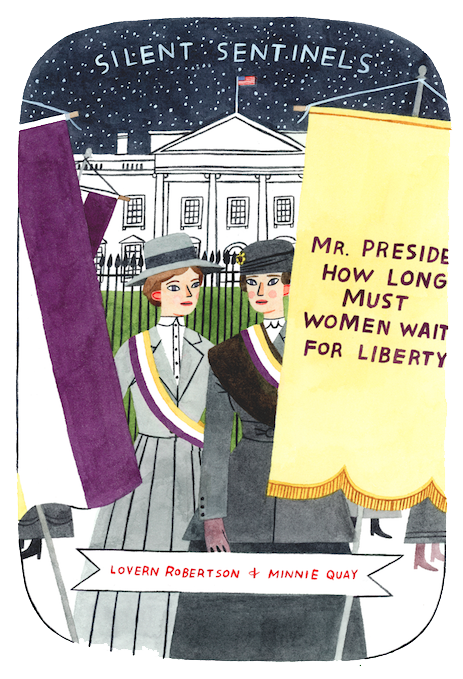

The Silent Sentinels,

Lovern Robertson & Minnie Quay

1917-1919

“No sacrifice is too great.”

– Minnie Quay

By Rebekah Clark

Historical Research Associate, Better Days 2020

Utah suffragists Lovern Robertson[1] and Minnie Quay[2] were so committed to fighting for the national suffrage amendment that they joined one of the most famous protests by the National Woman’s Party and participated in picketing the White House in 1917, ultimately becoming victims of the infamous “Night of Terror.” Their courage and determination contributed to the eventual success of the Nineteenth Amendment.

Utahn Lovern Robertson (4th from left) stands with her fellow suffragists, The Silent Sentinels, on November 10, 1917. Library of Congress.

On January 10, 1917, a dozen suffragists from the militant National Woman’s Party began picketing the White House, an unprecedented move by any protesters at that time. For the next two and a half years, almost 2,000 women took turns picketing outside the White House six days a week until the suffrage amendment finally passed both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives on June 4, 1919. These “Silent Sentinels of Liberty” carried large banners that accused President Wilson of hypocrisy for fighting for world democracy in World War I while leaving American women without rights. While the controversial protesters were supported by some onlookers, they were harassed, ignored, and attacked by others and began to be arrested starting in June. Following the arrest of leader Alice Paul, the largest group of protesters in the whole campaign gathered at the White House on November 10, 1917.

Minnie Quay in 1917. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Lovern Robertson and Minnie Quay, suffragists from Salt Lake City, were among the 41 picketers from 16 states who protested on November 10 and were arrested for obstructing traffic. Aware of the risk of censure, Lovern had stated just prior to leaving Utah: “I do not expect to escape arrest.”[3] Both women had been active in politics for many years. Lovern belonged to the Socialist party and was deeply committed to the cause of suffrage. As a young adult, Minnie had visited her older sister in Wyoming and allegedly stayed a year just so she could vote. Her husband later stated that “she never has forsaken the cause of suffrage since she cast her first vote.”[4] After the arrest of the November 10th protestors, Minnie was chosen to address the court during their trial. Unsuccessful in their demands for treatment as political prisoners, the suffragists were sentenced to thirty days in prison.

On the night of November 14, 1917, known as the “Night of Terror,” the suffragists were transferred to the Occoquan Workhouse where the prison superintendent ordered approximately 30 guards to brutalize the imprisoned suffragists. Several of the women were chained, beaten, choked, and even violently force fed when they engaged in a hunger strike. Minnie Quay detailed the indignities suffered in a letter she sent to her husband from prison, describing how the prison guards “employed incredible brutality.”[5] She also stated in a notarized affidavit following the ordeal that she was dragged in the dark to a filthy freezing cell and the superintendent threatened to use straitjackets, gags, handcuffs, and the whipping post.[6] Lovern Robertson similarly described the violence against the women, testifying by affidavit that she heard the superintendent guarantee that “these men will handle them rough” and then order that Lovern and others be kept away from the leaders of the group, whom he said ought to be “locked up in solitary confinement for the rest of their lives” or “taken out and shot.”[7] Both Utah suffragists spent much of their time in the prison hospital before their early release on November 29.

Lovern Robertson. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Despite the trauma of this experience and opposition from more conservative suffragists in Utah, Lovern Robertson and Minnie Quay remained committed to the suffrage cause. Reflecting the opposition of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) to the militant tactics of the National Woman’s Party, Utah’s predominant suffrage organization immediately sought to distance itself from the radical protests. When Minnie joined the picketing line, the Woman’s Democratic Club (a NAWSA affiliate) terminated her membership, refunded her dues, and officially condemned her participation in the National Woman’s Party protest. In a published letter, signed by Utah State Suffrage Association president Emily S. Richards and Democratic Woman’s Club president Hortense Haight Nebeker, the more mainstream organizations “publicly denounced the tactics of this militant group of women” and criticized Minnie’s personal political sincerity.[8] Undaunted, Minnie received an “urgent appeal” from the National Woman’s Party just weeks after her arrest, asking that she return to Washington, D.C. immediately to participate in a mass picket protest. She replied, “If I am needed, I shall not hesitate to return at once. I am ready to do anything within my power and no sacrifice is too great.”[9]

The National Woman’s Party picketing the White House in 1917. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Although the protest was considered radical, the mistreatment of the Silent Sentinels angered many Americans and created more sympathy for the suffrage movement. The next year, President Wilson dramatically reversed his stand on women’s suffrage and gave a speech in support of the suffrage amendment. By the time the suffrage amendment became law in 1920, a U.S. Court of Appeals had cleared the Silent Sentinels of all charges for their civil disobedience, creating an important legal precedent that paved the way for generations of protestors.

Many thanks to Ardis Parshall for sharing the identity of Utah’s Silent Sentinels with our team.

Footnotes

[1] Ellen Lovern Adair was born into a polygamous family on January 3, 1880 in Orderville, Utah, married blacksmith Charles Thomas Robertson on April 27, 1898 in Manti, Utah, and died in Los Angeles, California on September 13, 1950. She raised three sons to adulthood and had three children die at birth. She ran a boarding house in Salt Lake City for several years. While some newspaper and census records use alternative spellings of “Laverne,” “Lavern,” “La Verne,” or most commonly “Mrs. C.T. Robertson,” we have chosen to adopt the “Lovern” spelling used on her headstone and marriage certificate.

[2] Mary “Minnie” McCluster Prior was born in California on November 20, 1863 and died in Salt Lake City, Utah on February 15, 1946. On April 27, 1905, she married Robert B. Quay, a prominent Salt Lake City businessman. When her husband was elected postmaster in Garfield, Utah, ca. 1907, Minnie was appointed assistant postmaster.

[3] “Salt Lake Woman to Picket White House,” Salt Lake Tribune (November 1, 1917).

[4] “R.B. Quay Will Stand Back of His Militant Spouse,” Salt Lake Telegram (November 4, 1917).

[5] “Quay Challenges Kent to Join Suffrage Pickets,” Salt Lake Telegram (November 18, 1917).

[6] “Affidavit of Minnie P. Quay,” November 28, 1917, Library of Congress.

[7]“Affidavit of Mrs. C.T. Robertson,” November 28, 1917.

[8] “Say Mrs. Quay is Not a Democrat,” Salt Lake Tribune (October 31, 1917); “Mrs. Jenkins Hires White House Pickets,” Salt Lake Telegram (October 31, 1917); “Suffragist Leaves for Washington,” Salt Lake Tribune (October 30, 1917). Minnie Quay’s political allegiance did in fact shift over time. Strong-minded from the start, she allegedly first voted for the Democratic ticket despite the fact that her brother-in-law was running for Republican county sheriff. Upon her appointment as assistant postmaster, she joined her husband in the Republican party and was later elected as a state Republican convention delegate in 1916. Shortly thereafter, she once again switched parties and joined the Woman’s Democratic Club on February 14, 1917, was elected as a district chairman for the Democratic party in 1918, and spoke to 650 delegates at the Democratic State Convention on June 14, 1920. Her active political participation and commitment to women’s suffrage, however, remained consistent throughout her life.

[9] “1000 Pickets Will Heckle Wilson, Says Mrs. Quay,” Salt Lake Telegram (December 20, 1917); “Salt Lake Woman to Be Picket,” Ogden Daily Standard (December 21, 1917).