UTAH WOMEN’S HISTORY / Imagery and Strategies Used in the Women’s Suffrage Movement: Developing a Get-Out-the-Vote Campaign

Imagery and Strategies Used in the Women’s Suffrage Movement: Developing a Get-Out-the-Vote Campaign

Lesson Overview

Students will analyze primary source documents from the women’s suffrage movement–both nationally and in Utah–to examine the tactics, strategies, and imagery used in this social movement. They will also evaluate the effectiveness of these tactics and strategies in affecting social and civic change. As an optional step, students will use this information as the means to creating their own campaigns to encourage Utahns to register to vote and cast votes.

Recommended Instructional Time: 1-3 class sessions

Historical Background for Educators

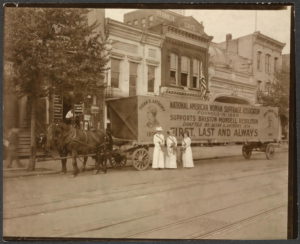

In 1890, the two rival suffrage associations, the American Woman Suffrage Association and the National Woman Suffrage Association, merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). NAWSA united suffragists in one association for the first time and it coordinated the national effort for suffrage through state and local groups, newsletters, and annual conventions. Although Elizabeth Cady Stanton was nominally the first president of NAWSA, Susan B. Anthony essentially led the organization from 1890 until 1900, when Carrie Chapman Catt became the next president.

Three women stand in front of a horse-drawn wagon with a sign supporting the NAWSA. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

At the national level, NAWSA did not prevent African-American women from becoming members, but state and local associations often did. This led many African-American women to form their own, separate suffrage organizations. The National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC) merged several black women’s social clubs in 1896 to support women’s suffrage along with issues of great importance to black women such as anti-lynching efforts.

Women in the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs.

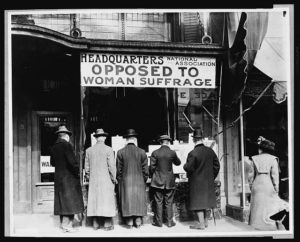

NAWSA continued the work of its two founding organizations by pursuing the tactics that had been used for decades: petitioning and lobbying legislators at both the state and national levels. Utah suffragists worked with the NWSA and then NAWSA to push for a women’s suffrage clause to be included in Utah’s state constitution adopted in 1895. Although women gained suffrage in four western states in the 1890s (Wyoming in 1893, Colorado in 1893, and Utah and Idaho in 1896), the next state victory would not come until almost a decade and a half later, when women gained voting rights in Washington state in 1910. These long years in between are sometimes referred to as the “doldrums” of the suffrage movement. Many women and men organized against suffrage during this time period. Local anti-suffrage organizations had long existed, but a national anti-suffrage movement did not officially form until the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage was founded in 1911. Anti-suffragists, both women and men, argued that women did not want the vote, that they were incapable of making rational decisions about politics, and that political involvement would take them away from their family duties.

Headquarters of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

When Woodrow Wilson was elected President in 1912, NAWSA planned its first parade in Washington, DC for March 3, 1913–the day before his inauguration–to call for a constitutional amendment for women’s suffrage. President-elect Wilson had stated during the campaign that he believed suffrage was an issue for the states, not the federal government. Suffragists argued that just as the 15th amendment prohibited states from restricting suffrage based on race, another amendment was necessary to prevent them from doing so based on sex. NAWSA leaders planned the parade as a show of force and a way to gain publicity for the cause. Women had held suffrage parades before in states like New York, but it was still considered very unladylike for women to walk in the streets at that time. Still, nearly 8,000 women marched in the D.C. parade, ordered by state. Organizer Alice Paul, who had worked with more militant British suffragettes in the UK, asked black women to march in the back because many white women didn’t want to march next to black women. Many black women did march in the back, but several black suffragists, including Ida B. Wells-Barnett, ignored this direction and marched with their states anyway. This was just one example of the ways white women often sidelined black women and their interests in the women’s rights movement. During the parade, suffragists were heckled, tripped, and even assaulted by crowds in town for the inauguration, and the D.C. police failed to step in (the police’s refusal to protect the suffrage marchers led to congressional hearings and cost the D.C. police superintendent his job). About 100 marchers ended up in the hospital, but their mistreatment made the march a major news story and drew national attention.

1913 Suffrage Parade. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

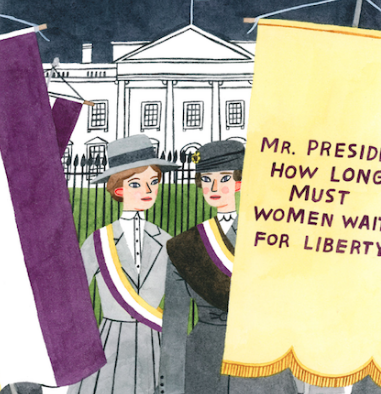

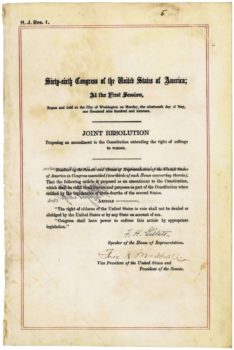

After the 1913 parade in Washington, Alice Paul wanted to organize more parades and protests to get the public’s attention (following in the footsteps of militant British suffragettes), but NAWSA leaders opposed the idea because they didn’t want to be seen as too radical. Paul and others broke away to form the Congressional Union in 1913, which was later renamed the National Woman’s Party (NWP) in 1917. Both NAWSA and the NWP were connected to Utah suffragists, with national leaders coming through Utah several times in the 19-teens to hold rallies and gather signatures on petitions for a national suffrage amendment. However, more traditional Utah suffragists did not support the NWP’s tactics. From their headquarters on Capitol Hill in D.C., the NWP organized the first pickets of the White House, starting in January 1917, where “silent sentinels” held banners criticizing President Woodrow Wilson for his lack of support for a national women’s suffrage amendment. They refused to stop picketing when the U.S. entered World War I later that year, and many women were arrested for obstructing traffic on the sidewalk, including two Utah women, Minnie Quay and Laverne Robertson. Several women went on hunger strikes in prison and were force-fed, and the newspaper reports garnered public sympathy for the cause. After President Wilson announced his support for a women’s suffrage amendment, Congress passed the 19th Amendment in the spring of 1919. Once 36 states voted to ratify it, the Amendment became law on August 26, 1920.

Very first suffrage picket line on January 10, 1917. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

The 19th Amendment removed gender restrictions on voting and was a huge victory for the 70+ years long fight for women’s suffrage. Still, there were many women (including Native-American and Asian women) who still could not vote because they lacked citizenship due to racially-discriminatory citizenship laws. American Indians did not gain voting rights until 1924, when Congress granted them U.S. citizenship through the Indian Citizenship Act. Still, many states, including Utah, made laws and policies which prohibited American Indians from voting, claiming that American Indians living on reservations were residents of their own nations and thus non-residents of the states. In 1957, the Utah legislature finally repealed the legislation that prevented American Indians living on reservations from voting, becoming the one of the last states in the U.S. to do so.

Key Utah State Standards Addressed

Social Studies

Content Standards

- U.S. II Standard 2.3: Students will evaluate the methods reformers used to bring about change, such as imagery, unions, associations, writings, ballot initiatives, recalls, and referendums.

- U.S. II Standard 2.4: Students will evaluate the short- and long-term accomplishments and effectiveness of social, economic, and political reform movements.

Literacy in Social Studies Standards

- Reading for Literacy Standard 1: Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, connecting insights gained from specific details to an understanding of the text as a whole.

- Reading for Literacy Standard 7: Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in diverse formats and media (e.g., visually, quantitatively, as well as in words) in order to address a question or solve a problem.

- Reading for Literacy Standard 9: Integrate information from diverse sources, both primary and secondary, into a coherent understanding of an idea or event, noting discrepancies among sources.

- Writing for Literacy Standard 1: Write arguments focused on discipline-specific content.

Learning Objectives

- Students will analyze and evaluate the effectiveness of the tactics and strategies used by women’s suffrage organizations.

- Students will create a campaign to persuade women in Utah to register to vote/vote.

Guiding Questions

- How are similar tactics used across social movements? What tactics tend to be the most effective in effecting change?

- How did the women’s suffrage organizations use tactics to persuade people to their cause?

- How do more moderate groups doing x benefit from more radical groups doing y? And vice versa?

- How have today’s social and political reforms been affected by those that took place from the 1880s to the 1920s? How are these past arguments reflected in women’s issues today?

- How did race play a role in the women’s suffrage movement? How did this impact the effectiveness of the 19th Amendment in granting all women voting rights in the U.S.?

- How do race, gender, and class intersect in social movements?

Vocabulary

(noun) a change in the words or meaning of a law or document (such as a constitution)

The 19th Amendment in the U.S. Constitution grants women voting rights.

(noun) a ticket or piece of paper used to vote

Seraph Young was the first woman in the modern United States to cast a ballot in an election.

(noun) a series of events designed to influence voters in an election

Suffragists like Susan B. Anthony led the campaign for women’s voting rights.

(verb) to take part in a series of events to influence voters

Suffragists campaigned for women’s voting rights.

(noun) a representative who votes on behalf of others

Susa Young Gates was one of many delegates representing the women of Utah at national suffrage conventions.

(noun) To give someone the right to vote

Emmeline B. Wells was a Utah leader involved in the enfranchisement of women.

(verb): to try to influence government officials to make decisions for or against something.

Anti-polygamists lobbied Congress to make polygamy illegal.

(noun) People who are assumed to “listen to reason;” committed to “friendly persuasion;” push social norms a little, but still within levels of respectability.

Carrie Chapman Catt was a leading suffragist who was considered more moderate; she favored continuing to use tactics that had been used during previous decades and keep herself in the good favor of male leaders.

(noun) People who express greater degrees of dissatisfaction than moderates; they tend to be more “combative” and push more against social norms and ideas; more extreme.

Radicals tend to make moderates look more conservative or acceptable.

Alice Paul was considered radical because of her White House protests.

(verb) to make official by voting for and signing (a constitutional amendment)

In August 1920, the 19th Amendment granting women’s voting rights was ratified by three-fourths of the states.

(noun) The right to vote in a political election

During the women’s suffrage movement, women fought for and won the right to vote in political elections.

(noun) a person who worked to get voting rights for women

Suffragists fought for women’s voting rights.

Materials Needed

Lesson

Building and Activating Background Knowledge

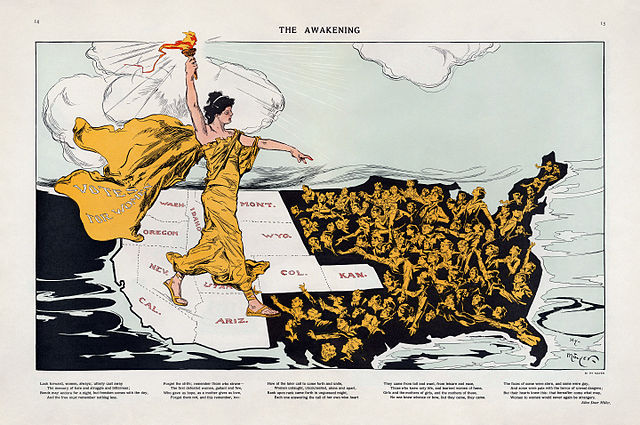

- Show students the cartoon by Henry Richards, “The Awakening,” Puck, 1915. The PowerPoint has these images. Ask them to share what they notice: What stands out to them? What questions do they have? What is this cartoonist wanting to convey? What might this tell us about the women’s suffrage movement at this point in time? What does this suggest about Utah’s involvement and role in the movement?

- Compare “The Awakening” with the 1920 map of women’s suffrage. Ask students what they notice. How does this map compare to “The Awakening”? Point out that no states granted suffrage from 1896-1910. Why might this be the case? Make sure to note that women in Utah Territory actually got voting rights first in 1870, then had them taken away in 1887, and had them returned in 1896 with statehood. Read more here. Or watch the short video about this history.

- Use chart of suffrage organizations to discuss these organizations’ leadership, goals, and tactics. There are images of the key leaders from these organizations in the PowerPoint. Various organizations, groups, and individual leaders may all have a common goal (i.e. women’s suffrage), but they may disagree about the overall best strategies and tactics to achieve these goals. For example, the AWSA favored a state-by-state approach to winning women’s suffrage, while the NWSA advocated for a national amendment approach. As students look over the chart of suffrage organizations, ask them to consider the following questions:

- What was the purpose of creating suffrage organizations? What were these organizations able to do and accomplish that individuals could not have done on their own?

- What similarities and differences do they notice in these organizations?

- Why did organizations split and merge?

- What are the pros/cons of a state-by-state approach vs federal amendment approach to winning women’s suffrage?

- What questions do students still have about these organizations?

- Review key vocabulary, specifically discussing the difference between moderate and militant/radical strategies and tactics.

Analyzing Primary Source Documents

- Memorabilia, speeches, newspapers, women’s rights conventions, petitions, parades and public protests were some of the tactics used during the suffrage movement.

- Showcase the following primary sources of tactics used by suffrage organizations in a gallery format on the walls around your classroom or in stations where groups of students rotate. You might also assign groups of students to a set of documents and then have them share their findings to the class. Students should use the graphic organizer to direct their thinking and analysis.

- Memorabilia. Select from the following:

- Utah-specific memorabilia (found in materials)

- National memorabilia (select from the following sources):

- The National Women’s History Museum has curated an online exhibit entitled “Creating a Female Political Culture” that provides an overview of memorabilia.

- Woman Suffrage Memorabilia

- Ann Lewis Women’s Suffrage Collection

- The National Museum of American History

- National Women’s History Museum

- Petitions, Speeches & Conventions

- Suffrage Newspapers

- 1913 Suffrage Parade

- 1915 Suffrage Envoy

- Silent Sentinels and Hunger Strikes (1917-1919)

- Memorabilia. Select from the following:

- Have students complete the graphic organizer and answer the evaluation and reflection questions. They will need the “Reasons For/Against Women’s Suffrage” chart to respond to the first question.

- You may want to complete the story of this history by discussing the ratification of the Amendment. The PowerPoint includes images related to ratification.

Assessment

- You may choose to end the lesson here using the students’ responses to the evaluation and reflection questions as the assessment OR you may choose to stage a suffrage parade/debate with students creating their own memorabilia OR you may decide to have students use what they have learned regarding strategies and tactics to develop a campaign to increase voter participation.

- Over the past 30 years, Utah women’s voter participation has been steadily decreasing. Utah women’s voting turnout is the lowest in the nation. Now that students have studied the organizations created by and tactics used by suffragists, students will use this knowledge to create a campaign to improve voter registration and turnout amongst Utah women (or they could create a campaign to persuade women to run for elected office or to improve turnout of other eligible voter groups). Teaching Tolerance has great teacher and student resources about voting.

- Find information about Utahns’ political involvement:

- Students can work individually, in pairs, or in groups. They can use the planning sheet to direct their thinking about their campaign. It asks them to consider the following:

- A name and slogan for the campaign

- Their objectives for the campaign

- Tactics–what will they do to persuade women (or others) to vote? (i.e. posters, protests, parades, flyers, speeches, petitions, ads, buttons, etc)

- What imagery will they use?

- You may decide to have students produce the items for their campaign (total number of type of items are up to teacher’s discretion) and provide a rationale for their choices.

- You may also want to examine some of the various voter registration initiatives that already exist in Utah:

- Evaluate students campaigns based on their ability to provide a cohesive plan with a strong rationale for their choices. You may choose to use the provided rubric.

- Have students present their campaigns to their peers & rate how effective they think the campaign will be.

Adaptations

- Have students look solely at the memorabilia from the National Women’s History Museum online exhibit instead of all of the documents provided.

- Analyze the primary-source documents as a group or whole class.

- Look at one primary-source document as opposed to several documents together.

- Students may produce items that could have been used in the suffrage movement instead of a present-day campaign.

Extensions

- Examine how voting rights have historically been tied to property ownership and citizenship. Look specifically at the wording of the 14th and 15th Amendments. What stipulations on voting did these Amendments enforce? How do these Amendments build on each other? Does the language explicitly exclude based on sex? Why might suffragists not support the 15th Amendment?

- Discuss how the extension of rights to some groups might pave the way to extending rights to other groups. How might extending rights to only some groups make it more challenging for other groups to get the same rights? For example, white women gained voting rights before women of color, but some would argue that the 19th Amendment was a first step towards guaranteeing the rights of minority groups.

- Compare/contrast the tactics used nationally with what happened in the West regarding suffrage, especially in Utah. Read the review of How the Vote was Won: Woman Suffrage in the United States, 1868-1914 by Rebecca Mead for background information on the suffrage movement in the West.

- Learn more about Utah women who were advocates and who were involved in the suffrage movement. What are the similarities and differences between these Utah women activists and national activists? What tactics did Utah women use that are similar/different to those used by national activists?

- The 14th, 15th, and 19th Amendments did not provide voting rights for Native Americans and many states used restrictive laws and means to prevent African Americans from voting. What imagery and tactics were used to fight for voting rights for these other groups? Compare suffrage imagery and tactics to the imagery and tactics used in these other movements.

- Read about Utahns Lavern Robertson and Minnie Quay who were involved in the The Silent Sentinels. What additional information do learn the events and conditions during the “Night of Terror”?

- Many of the national suffrage organizations did not include black women and their concerns. The individuals involved in the NACWC continued to work for their rights in spite of the white-dominated suffrage organizations’ efforts to exclude them. How did women of color continue to fight for their rights after the passage of the 19th Amendment?

- Examine the Voting Rights of 1965–legislation that outlawed the discriminatory voting practices adopted in many states. Why was this legislation necessary if the 19th Amendment supposedly granted women the vote?

- In 1957, the Utah state legislature repealed the legislation preventing Native Americans living on reservations from voting–one of the last states to do so. Learn about the history of Native American voting rights in the United States and compare this history with the voting rights history of other groups.

- The 1913 women’s suffrage procession was the first mass public demonstration by women in the United States. Compare this procession with later marches in Washington D.C. For more information about large marches and protests in D.C, read “Eleven Times When Americans Have Marched in Protest on Washington” in the Smithsonian Magazine.

- Provide students with the chart of pro- and anti-suffrage arguments. Have them discuss with a partner or as a whole class re: what stands out to them about these arguments? Do they find any of these arguments convincing/not convincing? Why? What similar arguments do they notice being used in women’s movements today? Or used in other progressive movements?

Tell us your experience

We’d love to hear about your experience in using this lesson to engage with your students so that we can better serve those who choose to use this lesson in the future.

Share Your Experience