UTAH WOMEN’S HISTORY / Analyzing Opinions For and Against Women’s Suffrage in Utah, 1870-1896

Analyzing Opinions For and Against Women’s Suffrage in Utah, 1870-1896

Lesson Overview

In this lesson, students will analyze primary source excerpts from various viewpoints. Students will use these sources to interpret why most Utah women’s voting rights were granted, rescinded, and returned between 1870 and the achievement of statehood in 1896. Proceeding this document analysis, students will participate in a voting simulation activity to consider the effects of franchisement, disfranchisement, and re-enfranchisement, and the role suffrage played in Utah’s quest for statehood.

Recommended Instructional Time: 1-2 Class Periods

Historical Background for Educators

In the nineteenth century, many leaders and members of the Utah-based Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints practiced polygamy, which was a religious belief of the church. Though there were no federal laws against polygamy when the Latter-day Saints began practicing this marital system in the 1840s, polygamy was strongly opposed by the American mainstream, which valued monogamous marriage. Polygamy was so unpopular that in the mid-1850s, the newly emerged Republican Party adopted a platform of ending the “twin relics of barbarism”–slavery and polygamy.

“[Utah women] have held the ballot sacred and have always been on hand to exercise the right and cast their votes for the men of their choice.” –Emmeline B. Wells

As anti-polygamy laws and sentiment strengthened in the United States, Latter-day Saints in Utah wanted to show that Mormon women were not duped, oppressed, or “enslaved” by polygamy as they were typically portrayed. Many Mormon women wanted to demonstrate that they, too, supported polygamy as a religious belief. On February 12, 1870, Utah’s territorial legislature granted voting rights to “every woman of the age of twenty-one years who has resided in this Territory six months next preceding any general or special election, born or naturalized in the United States, or who is the wife, widow or the daughter of a native-born or naturalized citizen of the United States.” Just as the Mormons believed would happen, Latter-day Saint women in Utah did not vote for representatives opposed to polygamy, but rather those who supported it.

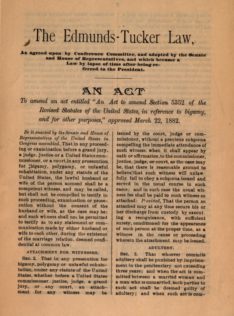

When anti-polygamists like Angie Newman saw Mormon women use their new political power to support polygamy, they lobbied for federal legislation to force an end to the practice–legislation that included rescinding the voting rights of Mormon men and all Utah women. The 1887 Edmunds-Tucker Act achieved this end. Mormon women suffragists, led by Emmeline B. Wells, fought to retain their voting rights and, after they lost them, lobbied to win them back.

In 1890, the LDS Church officially disavowed the practice of polygamy. Though Utah Territory had unsuccessfully applied for statehood several times over the previous four decades, the church’s disavowal of polygamy increased Utah’s chances of being admitted to the Union as a state. In 1894, Congress passed the Enabling Act, which essentially invited Utah to apply again for statehood. At Utah’s 1895 Constitutional Convention, delegates (who legally could only be male) debated whether to include a clause in the state constitution that would grant Utah women the right to vote and hold public office.

“To pursue this issue and adopt woman’s suffrage in the Constitution will endanger its life.” –B. H. Roberts

Delegate B. H. Roberts was one of the few who argued against the suffrage clause. But most of the delegates, like Franklin S. Richards and Orson F. Whitney, favored women’s suffrage. Backed by strong lobbying from female suffragists, the pro-suffrage delegates carried the day, and the clause for women’s suffrage was included in the proposed state constitution. Utah’s all-male electorate voted overwhelmingly to approve the constitution in November 1895, Congress ratified it, and President Grover Cleveland signed it on January 4, 1896. Utahns rejoiced not only that they had become a state, but also that Utah women were now able to vote again, as well as hold public office.

The U.S. Constitution gives each state control over its voting qualifications and election systems.

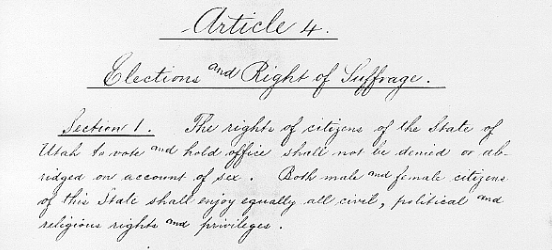

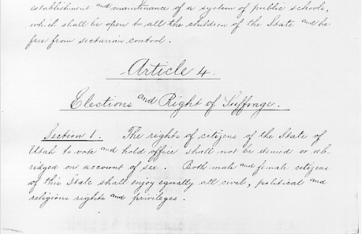

It is important to note that not all women residing in Utah were granted the vote in 1870 or with statehood in 1896 or with the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920. Utah women who were granted voting rights in 1870 only included “every woman of the age of twenty-one years who has resided in this Territory six months next preceding any general or special election, born or naturalized in the United States, or who is the wife, widow or the daughter of a native-born or naturalized citizen of the United States.” And in 1895, the Utah State Constitution stated: “The rights of citizens of the State of Utah to vote and hold office shall not be denied on account of sex.” Thus, only those who were considered citizens were allowed to vote. So, for example, since Native Americans were not considered U.S. citizens during this time period, they were excluded from women’s voting rights in Utah in 1870 and 1896, and nationally in 1920. American Indians gained voting rights when Congress granted them U.S. citizenship through the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924. Many states, including Utah, nonetheless made laws and policies which prohibited American Indians from voting, claiming that American Indians living on reservations were residents of their own nations and thus non-residents of the states. On February 14, 1957, the Utah state legislature repealed its legislation that had prevented American Indians living on reservations from voting, becoming one of the last states to do so.

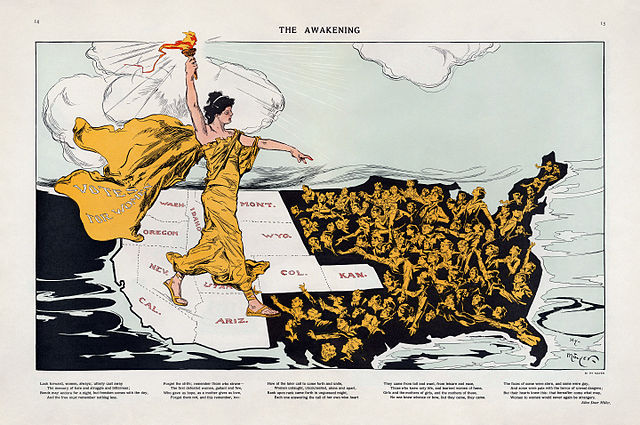

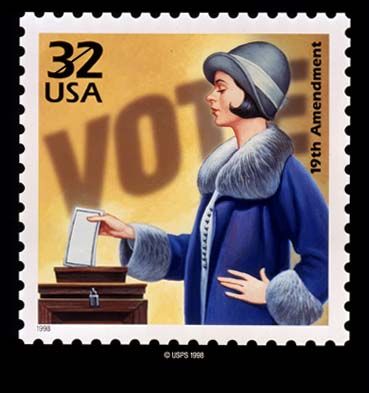

Article 4, Section 1 from the Utah State Constitution, Elections and Right of Suffrage.

The United States system of government, as a representative democracy, relies on citizens to vote and elect representatives to act on their behalf. Founding father James Madison said, “The definition of the right of suffrage is very justly regarded as a fundamental article of republican government.” The U.S. Constitution does not explicitly guarantee a right to vote, but in the absence of a specific enumerated federal law, the Constitution gives each state control over its voting qualifications and election systems. This principle of federalism explains why some states were able to adopt women’s suffrage sooner than others. It also explains why certain constitutional amendments have been necessary to expand voting rights and protections at a national level. While states still maintain control over voting requirements, constitutional amendments have been ratified over time to prohibit discriminating against voters based on factors such as race (15th Amendment); sex (19th Amendment); failure to pay a poll tax (24th Amendment); and age, for those 18 years or older (26th Amendment). These national amendments have extended voting rights to large groups of citizens who were historically denied suffrage.

Key Utah State Standards Addressed

Utah Studies

- Introduction: Students will craft arguments, apply reasoning, make comparisons, and interpret and synthesize evidence as historians.

- 2.4: Students will research multiple perspectives to explain one or more of the political, social, cultural, religious conflicts of this period (1847-1896).

- 2.7: Students will identify the political challenges that delayed Utah’s statehood and explain how these challenges were overcome.

English Language Arts

- Writing Standard 1: Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence.

Learning Objectives

- Students will be able to explain the arguments for various viewpoints on women’s suffrage in Utah.

- Students will be able to use primary-source excerpts to write a persuasive argument.

Guiding Questions

- What roles did polygamy and suffrage play in Utah’s struggle for statehood?

- What reasons did individuals and groups have for supporting or opposing women’s suffrage in Utah? How and why did these attitudes and reasons change over time?

- How did people of this time period try to influence voters and politicians to support or oppose women’s suffrage?

- What role did ethnicity play in the women’s suffrage movement?

- How can I influence my legislators’ support or opposition for legislation and causes?

Vocabulary

(noun) To take away someone’s right to vote

The Edmunds-Tucker Act caused the disfranchisement of Utah women.

(noun) To give someone the right to vote

Emmeline B. Wells was a Utah leader involved in the enfranchisement of women.

(noun) (in this context) individuals who were not Mormon

The Transcontinental Railroad brought many Gentiles to Utah.

(adjective) evil or immoral

Anti-polygamists believed that polygamy was very nefarious and worked to get rid of it.

(verb) to make it so something has no legal power

The law was nullified by the court, so people no longer had to obey it.

(noun) A marriage system in which a person is married to more than one person at a time.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints practiced polygamy, in which some husbands had more than one living wife.

(noun) The right to vote in a political election

During the women’s suffrage movement, women fought for and won the right to vote in political elections.

(noun) to publicly state that someone or something is wrong or bad

Susan B. Anthony denounced legislation that took away Utah women’s voting rights.

(verb) to officially accept or allow something

The LDS Church sanctioned women’s suffrage, supporting efforts made by women to win back their voting rights.

(adjective) providing a quick and easy way to solve a problem

Anti-polygamists believed that granting Utah women voting rights was expedient to ending polygamy.

(verb) to agree

Most delegates at the Utah State Constitutional Convention concurred that women’s suffrage be included in the proposed constitution.

(noun)

to give back someone’s right to vote

“Re” = to do again

The re-enfranchisement of Utah women occurred when Utah attained statehood.

(n) the right to vote

The 19th Amendment granted the franchise to women.

(v) to give the right to vote

The 19th Amendment franchised women.

Materials Needed

Lesson

Activating and Building Background Knowledge

- Voting Simulation: Students will first participate in three mini-elections as a way to understand that Utah women were granted the vote in 1870, lost their voting rights through the Edmunds-Tucker Act of 1887, and had their voting rights reinstated through Utah’s State Constitution which was accepted by Congress and U.S. President Grover Cleveland in 1896. Students will respond to a quick-write or a partner share at the conclusion of the voting simulation.

#I: Only One Enfranchised Group

- Decide ahead of time on an action for students to vote on (i.e. length of free class time or silent reading time, type of reward, favorite candy, etc.)

- Use the provided ballot template and fill it out to include at least two options for this vote.

- Show ballots to students and explain that they will vote for only one option.

- Distribute the ballots only to students who are wearing shoes with laces, explaining that voting rights are only extended to those wearing shoes with laces.

- After they have voted, collect and tally the votes.

- Announce the results.

#2: All Groups Enfranchised

- Now hold a second election. This could be the same item students voted on in the first mock election or it could be a different item.

- Using the template provided, create ballots that include at least two options for this vote.

- Show ballots to students and explain that they will vote for only one option.

- Distribute the ballots to all students.

- After voting, collect and tally the votes.

- Announce the results.

#3: One Group Disfranchised

- Return ballots from 2nd vote to students.

- Then ask for students wearing shoes without laces to return their ballots.

- Tear up these ballots, and do a recount of the vote.

- Announce the results.

Have all students respond to the quick-write and/or have them turn to a partner to discuss their responses to the quick-write questions.

4. Explain that throughout history, various groups have been denied and granted voting rights. Provide an overview of who could vote nationally and in Utah prior to 1870. Use the timeline on the home page as a reference.

5. Have students read “Receiving, Losing, and Winning Back the Vote” or provide an overview using the provided PowerPoint slides or watch the short video about this history. To help students keep track of the various groups and their changing opinions on women’s suffrage in Utah, you may have students take notes on the graphic organizer “Opinions on Women’s Suffrage in Utah: 1870-1895.”

6. After reading, ask them to discuss the following question either with a partner or as a class: “Reflect on your responses to the quick write. How do your experiences during the voting simulation compare to the experiences of women in Utah during this time period?”

7. Review vocabulary with students. You may wish for students to deepen their knowledge of key vocabulary by utilizing the “Key Vocabulary” worksheet.

Analyzing Primary Source Documents

- Options for grouping students (depending on time and skill level):

- More time: Students will analyze a total of four excerpts either in pairs or in small groups.

- Less time: Students will analyze a total of two excerpts in pairs (make sure these two excerpts are from the same time period for each pair). Assign pairs to one of the two time periods. Then, they will pair up with a different partner who analyzed two excerpts from the other time period.

- Note: Having students examine only one document does not illustrate how these documents speak to each other or provide adequate context for understanding these complicated arguments.

- Provide an overview of how these primary-source documents are structured. Point out to students that they should read the background explanation (at the top of the page) provided prior to the actual primary-source document to gain an understanding of what the primary-source document is about and who wrote it.

- As students read, tell students to consider why these speakers/writers held these viewpoints and why they used the reasons they did to support their claims. Students may make notes, ask questions, jot down ideas, etc. Questions at the end of each excerpt ask students to make conclusions and support their answers with evidence.

- You may have students complete the graphic organizer (there are two options provided) to organize the anti-suffrage and pro-suffrage arguments provided in each excerpt or have students highlight/annotate directly on the document.

- Depending on students’ skill level, you may decide to read and interpret one of the excerpts or a portion of an excerpt as a whole class before releasing students to work with partners/group members.

- Have students engage with the two opposing viewpoints within the same time period. Select from the options below or allow students a choice.

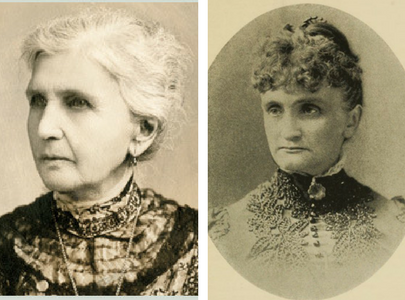

Angie F. Newman vs. Emmeline B. Wells

- Note: Background information on Newman and Wells is included on the student material. Have students discuss the background of each source.

- Taking away Mormon men’s and all Utah women’s voting rights through the Edmunds-Tucker Act in 1887 was one of many ways Congress pressured Mormons to stop practicing polygamy. Ask students to consider and write a response to the following questions: “Do you think Congress was justified in taking away women’s voting rights in an effort to end polygamy? Why or why not? Consider the opposing viewpoints of Newman and Wells in your response.” You may have students write their response in the form of a persuasive speech or petition or have them simply write an explanation of their position using evidence.

- Imagine it’s the day after the passage of the Edmunds-Tucker Act. Write postcards from the viewpoints of Angie Newman and Emmeline Wells to U.S. Congress. What might these two women write to their congressional leaders about this bill’s passage? How would their feelings differ?

B. H. Roberts vs. Franklin S. Richards OR Orson Whitney

- Note: Background information on Roberts, Richards, and Whitney is included on the student materials. Have students discuss the background of each source.

- Imagine you are one of B. H. Roberts’s constituents. Write Roberts a letter explaining why you do not support his opposition to including women’s suffrage. Use at least one of Franklin S. Richards’s (or Orson F. Whitney’s) reasons for supporting women’s suffrage in your letter.

- Imagine it’s the day after Congress has granted statehood to Utah. Write a postcard from the viewpoint of Franklin S. Richards or Orson F. Whitney to B. H. Roberts celebrating Utah’s statehood and the return of women’s suffrage. Then write Roberts’s response back to Richards or Whitney. What might these men write to each other?

Assessment

Students engage with opposing and similar viewpoints across time periods.

- Have students respond to the following prompts:

- What similarities and differences do you see in the anti-suffrage viewpoints during Utah women’s disfranchisement (Newman) versus re-enfranchisement (Roberts)? How did the disavowing of polygamy, religious background, and/or gender influence the similarities and/or differences?

- What similarities and differences do you see in the pro-suffrage viewpoints during disfranchisement (Wells) versus re-enfranchisement (Richards or Whitney)? Does polygamy, religious background, and/or gender seem to play a role in these viewpoints?

- If you have more time: Ask students to explain why women’s suffrage was granted to women, taken away, and returned using the viewpoints from the time period to support their explanation.

Adaptations

- Provide students with paraphrases of the original excerpts.

- Divide the paragraphs of an excerpt across pairs or groups of students (for example, group one would receive paragraph one, group two would receive paragraph two). Have pairs or groups determine the meaning of their assigned paragraph, and then, share these interpretations with the class. Or begin as an entire class examining the excerpts together before breaking students into pairs or groups.

- Have students complete the graphic organizer comparing the similarities and differences of viewpoints across the time period before composing their responses.

- Students may also provide verbal, instead of a written, responses to the assessment prompts.

Extensions

- A rebuttal to Angie Newman’s petition appeared in the Woman’s Exponent after the petition was presented to Congress. The chairman of the Democratic Party Committee in Davis County wrote B. H. Roberts a letter asking him to stop arguing against women’s suffrage. Have students read and analyze these responses. Reading these responses should only happen if students have read the primary-source documents in the main portion of the lesson.

- These excerpts were written by citizens trying to persuade politicians–or by politicians trying to persuade other politicians–to vote in certain ways. These individuals’ words influenced how people voted. Have students write (an email, postcard, or letter) to their local representative explaining why they would like their representative to vote for or against current legislation.

- Voting rights were denied to other groups during this same time period and for many years later. Have students compare reasons given by opponents to women’s suffrage and granting citizenship and voting rights to American Indians and other groups. How are they similar? How are they different? What reason and historical contexts may explain these differences?

- U.S. Congress took away voting rights in Utah with the Edmunds-Tucker Act in 1887. What are other instances when local, state, or federal government has placed restrictions on voting rights for certain groups. Why? What motivations underpin these restrictions? Do you agree or disagree that there are valid reasons for voting restrictions?

- Many rights are still denied to women throughout the world today. Compare reasons given by opponents to granting these rights to the reasons given by opponents to Utah women’s suffrage. For more info, read here.

- Women in Utah were civically-minded and engaged: voting in elections, running for political office, petitioning for causes, leading various political organizations. How does this involvement in the past compare to involvement by Utah women today? For more info, read here.

Tell us your experience

We’d love to hear about your experience in using this lesson to engage with your students so that we can better serve those who choose to use this lesson in the future.

Share Your Experience

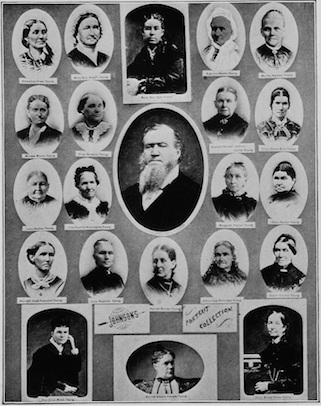

Image of Angie Newman & Emmeline Wells

Image of Angie Newman & Emmeline Wells  Image of B. H. Roberts & Franklin S. Richards

Image of B. H. Roberts & Franklin S. Richards  Image of B. H. Roberts & Orson F. Whitney

Image of B. H. Roberts & Orson F. Whitney